For those of you who support this newsletter and my writing through Patreon —thank you! Please consider lending your support in 2024.

Catching up on my six most recent column, in two tranches. Here’s the first tranche.

My end-year series on Government by Opinion

My columns for the last two weeks of December and and January 3 were part of a piece: the law of political inertia, versus the logical consequences of a previously-impossible majority mandate.

Political inertia describes the general unwillingness of players in the political system, to change its fundamental aspects because they have all learned to extract the most value from the system —and it’s shortcomings.

A political mandate, on the other hand —in particular, a majority mandate— is an incentive for change, even a demand for it. This is particularly so when built on the premise that the existing system is inferior to what came before, or needs an overhaul.

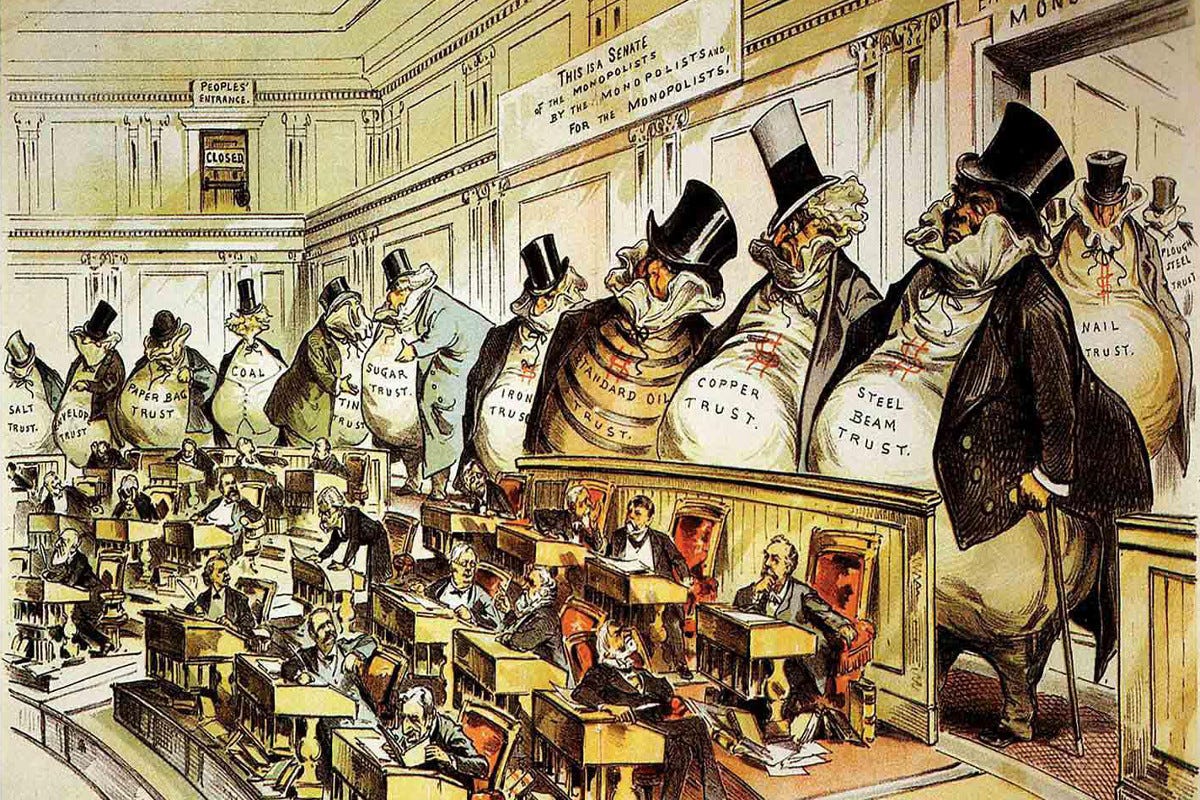

I explore both these themes in my year-ender (and year-starter) series. We have had a government of opinion since 1922: the question is, if we will have a government of the barons instead (to be sure, we have had a government of barons, locally; but the line was drawn, to a certain extent, nationally, precisely because of our having a government of opinion). The demise of opinion-makers and enforcers is what’s changed.

Government by opinion (1)

THE LONG VIEW

By: Manuel L. Quezon III – @inquirerdotnet

Philippine Daily Inquirer / 04:30 AM December 20, 2023

In 1922, the fundamental parameter that governs our national politics was established and has applied ever since. Usually given short-shrift by both academics and frustrated politicians (for reasons we will soon see), it was defined because of a split in the then-ruling Nacionalista Party and a showdown over the question of the role of public opinion in party politics. Who can claim to enjoy it? Who can be condemned for lacking it? How, in other words, to demonstrate you possess it? The key, of course, is elections, because elections conclusively prove who has public opinion on their side. The contest then becomes one of being to mold it, master it, and, thus, direct it (which is what academics wrestle with because it is ever-shifting, and, thus, difficult to measure, much less define: consistency is not just the hobgoblin of little minds, as Emerson famously despaired; it is the allergy of entire electorates, which also offends the tidy minds of frustrated politicos).

Magsaysay famously expressed it as “Can we defend it at Plaza Miranda?” which is why the signs of deterioration and the end game for the Third Republic were both signaled by grenades hurled at Plaza Miranda in 1947 and 1971. But even during the dictatorship, public opinion continued to be the ultimate arbiter: the annual or semi-annual plebiscites were meant to prove, in the absence of actually contested elections, that public opinion rested foursquare in the corner of the Great Dictator.

Which it did, arguably, from 1973 to 1981, as Marcos slowly, systematically, reversed the collective bargain he’d made with the political class in 1972 (abandon the 1935 Constitution with its limits on all of us, and I’ll give you a risk-free slice of the New Society, was the deal: senators, congressmen, constitutional convention delegates would all get guaranteed seats in parliament, while local governments that kowtowed would be excused from elections; justices in all the courts would keep their jobs if they kept quiet). Even as plebiscite after plebiscite proved to friend and foe alike that public opinion was on the side of the powers-that-be, the deal with various subsets of the powers-that-be got redefined—by the Supreme Power, the president. What 1983-1986 was, then, in contrast to 1978-1981, was a demonstration of how public opinion was emphatically no longer on the president’s side, which neutralized, slowly, and then surely, his coercive powers. The trinity of Philippine political theory and thought, such as it is (and such as it’s been practiced), lies in three observations. The earliest, from 1938, is that “The people care more for good government than they do for self-government … the fear is that the head of state may either exceed his powers or abuse them by improprieties. To keep order is his main purpose.” Virtually limitless authority and trust are bestowed on those who can promise order, but only so long as either tyranny or abuse are avoided. The second, from 1972, is “Nothing succeeds like success!” That to get away with the bold move is admired, so long as it succeeds; but if it fails, then public opinion will respond not just with derision, but electoral defeat. The third, coming from someone who served the presidents in 1938 and 1972 is, that the key to the presidency is to win and hold it “by shrewd and subtle manipulation of the Filipino psyche: an appeal, basically, to our common weaknesses: passivity, the love of spectacle, financial greed, and, most of all, the innate desire to have a leader who can make the decisions for us …” A tired and despairing conclusion except for the startling ability of Filipinos to recover their idealism—but perhaps once a generation only.

After 1986, public opinion has remained the arbiter of power as both the Marcoses and Aquinos found out: the fundamental difference being in Maria Ressa’s recollection of the late President Benigno S. Aquino III asking her, in alarm, about social media and whether that could possibly reflect reality, and the Marcos Restoration being built on a foundation of carefully, and ruthlessly, cultivated Alternative Reality: the key to the heartbreak of the former and the victory of the latter being a media that collapsed under the weight of its own arrogant conviction that it would always be, if not respected, then feared.

The primacy of public opinion remains even if, increasingly, it’s unclear who actually represents it, which strengthens the importance of elections. All the more significant that the centennial (1922 to 2022), when public opinion has been the parameter of power, was marked with the first majority presidency in a generation: the irony of a Marcos achieving what all the post-Marcos administrations tried to claim but only partially possessed: a majority mandate.

Government by opinion (2)

THE LONG VIEW

By: Manuel L. Quezon III – @inquirerdotnet

Philippine Daily Inquirer / 05:06 AM December 27, 2023

At first, the shock and awe in 2022, the centennial of our having a government by opinion, was in the realization that the Marcos Restoration could claim to be the new center, a generation after the old anti-Marcos coalition had claimed to be the center; something no longer tenable after the results were known. A year after that victory came the newer realization that even if it was a coalition that won, not every faction of that coalition could fully partake in the historic majority that was achieved. The coalition might have, on its marquee in bright political lights, the names Duterte, Estrada, and Arroyo but the name selected at the top of the ballot was only one: Marcos and it was that name alone that was given a majority.

To be sure, historic, too, was Duterte: as vice president but, as I’ve pointed out previously, if the presidency is limited by expectations (not just of performance, but conduct), so is the vice presidency. It must be seen to be subordinate, cooperative, and thus, loyal, to the presidency, otherwise it is politically punished by diminished public opinion. To a certain extent, much as public and media ignorance and political irresponsibility have tarnished public opinion surveys, the two main firms have maintained their political relevance because they remain professionally reputable (many of those who habitually slander them quietly still rely on them). While the mass media has lost much of its independence and audience, self-censorship or the unwritten rule that everything is fair game except the national management or ruling money ceases to apply when the public gets irritated, since usually this means the initial targets are underlings who are low on the bureaucratic and official pecking order. All sides can posture, as public opinion is formed.

Outside of elections, public opinion could be formed, and claimed, based on those willing to go through the inconvenience and risks of public protests, but here public opinion itself has changed and what is acceptable behavior has changed, too. In a sense some of the critics of people power are now the victims of their own success: having politically edged out those who claimed to represent it, they themselves cannot claim it for themselves: here, the Marcoses, Dutertes, Arroyos, and Estradas are all in the same boat. The Left has some leeway for what used to be dismissively described as “Agitprop” since permitting rallies and strikes allows officialdom to condescendingly claim it respects freedom of association and expression. But if it’s not exactly “Springtime for Hitler,” the spirit of the time is more conducive to the Right than the Left, just as the balance of forces favors the continuing liquidation of rebel guerrillas before they ever reach the point of being able to liquidate their liquidators (similarly, alliances of convenience can be made with radicals in the legislature whose electoral appeal has been proven to be manageably limited).

Armed, as it is, with a historic mandate and continuing popularity as far as it is usually measured, I expected there to be more of a concerted effort to reap the political rewards than proved to be the case until recently. The President, for one, proved to be surprisingly indifferent to party-building, and surprisingly inclined to put a brake on schemes to amend the Constitution. This eventually made sense as his political style emerged, in contrast to that of his father (or, to be more precise, the caricature that passes for public memory of his father on the part of admirers and detractors alike). Understanding his family dynamics and how he is far more of a conventional, establishment, figure than has been hitherto realized has also taken time—and is still unfolding. Just as the Marcoses of today actually represent the third restoration regime of our modern political history, the President, too, is the third specimen of a particular, post-independence type of president, namely the coddled crown prince motivated by past family trauma.

This, in turn, brings with it a fundamental shortcoming that, for the political class, at least, is the saving grace of this type: a lack of political imagination. So much so that out of loyalty to the memory of his parents, Benigno S. Aquino III would not challenge the system even when it was obviously failing; or Rodrigo R. Duterte would not change the system, even when one of his principal lieutenants laid out to him a scheme to create a radically revised one to replace it; or Ferdinand R. Marcos Jr. embracing at last, what every one of his post-1987 predecessors couldn’t risk but which the public has repeatedly said it would accept: a constitutional convention. He will seemingly only go where his uncle Fidel V. Ramos once tried going before.

Government by opinion (3)

THE LONG VIEW

By: Manuel L. Quezon III – @inquirerdotnet

Philippine Daily Inquirer / 05:00 AM January 03, 2024

Sen. Imee Marcos, who has that smart person’s gift—the ability to give reporters a cutting phrase on demand—dismissed the latest gambit by the House of Representatives to amend the Constitution by describing it as the kind of scheme proposed by only those unelectable to the presidency.

Her withering contempt was aimed at her first cousin, Speaker Martin Romualdez, who seems to enjoy a closer relationship, politically and personally, with her brother, President Marcos, than she does. She is, of course, a reelectionist whose political value needs to be validated by a return to the Senate, where she will both outlast her brother’s presidency and be of use to the ally she holds closer, the current Vice President. After all, just as Inday Sara can still dream of the presidency, Ate Imee can still dream of being veep.

This year is the calm before the storm in the sense that 2025, as the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism has pointed out, will feature not just the midterms but a total of three elections: two will take place in May: the national midterm elections and the first regular election in the Bangsamoro. The two elections being joined at the hip is a legacy of President Benigno S. Aquino III, who surprisingly convinced the political class to synchronize the two to forever prevent a return to the era of “dagdag-bawas.” Then, in December 2025, the barangay and Sangguniang Kabataan elections will be held, perhaps a convenient time for a constitutional plebiscite.

I have become convinced that much as the well-meaning and the simply irredeemably nerdy have long argued over what constitutional changes should be made, the reality of widespread public ignorance of the Constitution’s actual provisions and the despair of the constitutionally concerned (or obsessed) disguises an even more basic fact. And that is: not a single sector of government has any real reason to change the current system except, perhaps, for our presidents—which is why the system is designed to frustrate whoever is chief executive.

To be sure, the first problem has been one of authorship. The authors of our Constitution did an outstanding job in (accidentally, to be sure) coming up with a Charter impossible to amend. And what cannot be amended cannot be improved. For those sincerely alarmed by our having an operating system stuck in the Casio calculator era, convincing the public to care has proven impossible as public education has degraded and our civic sense has withered away.

For those motivated by political self-interest, it’s also proven a tall order as they refuse to run the (only public-acceptable) risk of an elected convention, and cannot think of changes that wouldn’t deprive the electorate of one of the few rights it cherishes—that of individually casting a vote for the head of state and government. You can try to make sense of the endless permutations of the endlessly failed efforts to change the Constitution, but I suspect that in the end, you will reach the conclusion that even among the proponents, there has never been a critical mass in favor of amending, much less changing, the system.

Local governments run the risk of their powers, both fiscal and political, being clipped. Senators fear being amended out of existence, and House representatives—who constitute a permanent majority able to extort funds and favors from whoever is elected president—run the risk of actually having to work or compete, or both. Even the Supreme Court and lawyers who enjoy the currently cozy system of selecting justices, with a high court enjoying greater powers than its predecessors, run the risk of their powers and discretion being rolled back, or even worse, a constitutional court being created. Far better to do what they have collectively done: humor presidents and speakers and cause a lot of largesse to be pointlessly handed out, to no avail.

President Fidel V. Ramos in retrospect was the last of our old-fashioned presidents, one devoted to what can be described as the Cult of the State: one of those who explored aggrandizing their power as it ultimately would enhance that of their office, which they and others viewed as the lynchpin of the state. This viewed both power and office as essential to achieving modernity.

Marcos, I’ve always argued, was fundamentally anti-modern, even pre-modern, even as he mastered the appearances of modernity by parroting the lingo of the technocrats on which he depends. But his ultimate ambition was a hereditary monarchy disguised as a presidency. I am less convinced his crown prince shares the same obsession. He has achieved political and social vindication by election on the traditional Filipino political principle that election provides absolution, and by being welcomed back into the ranks to which he always felt he belonged: that of the world’s ruling families.

All that remains is to ensure the security of the clan by achieving the resolution of his family’s legal problems on terms favorable to it. In other words, by being the one who upholds, and doesn’t subvert, much less disturbs or disrupts, the system. Which would explain his limited support for strictly economic-related provisions of the Constitution.