Love (Racketeering), Philippines

A trifecta of racketeering, extortion, and scofflawing

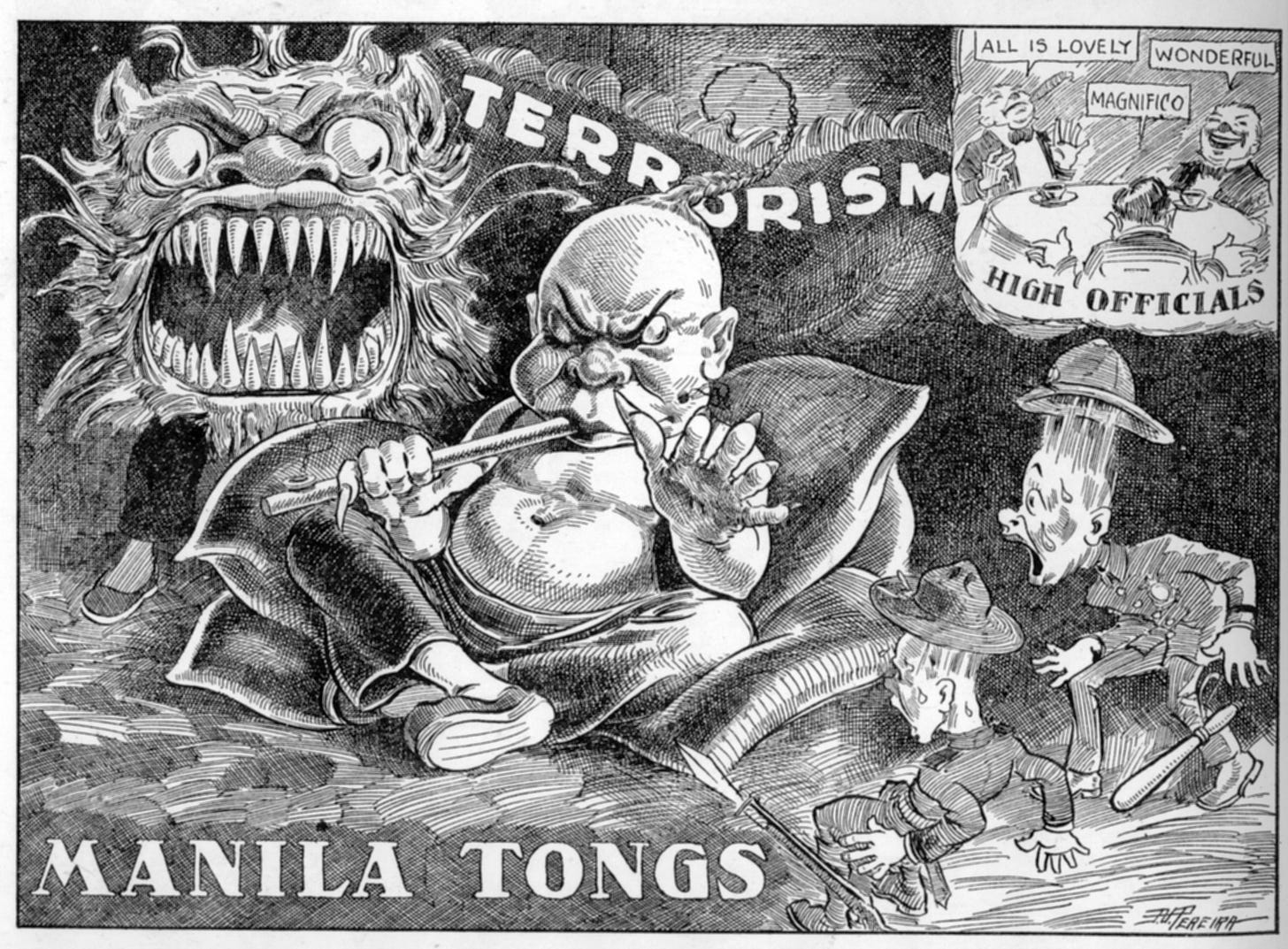

Some recent headlines and reports have gotten me thinking. So we were all obsessing over POGOs but we were missing the other half of story: at the height of POGOs was also the overlapping, it seems, eSabong phenomenon: with a likely connection to crooked local governments in the PRC and not just triads. Plus, there is the Philippines as a “safe space” for online racketeers, the latest manifestation of which are "pig butchering" ops. What they all have in common was they hit upon the trifecta of succesful gangsterism: a chaotic and mercenary bureaucracy, a compromised and obliging police, and political officials either on the take, locally, or who prove powerless to enforce national laws in regional or local fiefdoms. All under a blanket of a permissive yet hypocritical society when it comes to gambling.

As with all things both convenient and lucrative, the powers-that-be are content to turn a blind eye to it until too much of a good thing leads to the kind of excess that requires action to pacify a public outcry. Local barons run their fiefdoms with gory abandon until they indulge in one massacre too far; presidents can rake in gambling largesse until playing favorites leads to an impeachment; and, now, a gangland fight over online gambling can fester until the grisly expose of dozens being rubbed out gets too shocking to ignore.

Prologue: the Philippines as “safe space” for racketeers

A book remains to be written on the manner in which scams grab the headlines not least because of the large swathe they cut across class lines in our otherwise often highly compartmentalized society. Every so often, an event or article serves to tie together different stories —strands just waiting to form a thread of a larger story— such as I observed back in 2001:

[A]nother couple of books got me thinking that the colonial ties now include a 21st-century manifestation that goes beyond generations-old preoccupations such as “colonial mentality”: We are, in a strange, twisted, but thoroughly modern way, a kind of twisted Wild West hinterland of the United States.

The two books are “The Mastermind,” by Evan Ratliff, and “Playing Dead: A Journey Through the World of Death Fraud,” by Elizabeth Greenwood. The former book is about Paul Le Roux, who turned the profits from his network of prescription painkiller-peddling websites in the US into a criminal enterprise that he operated from the Philippines. The latter is an examination of the different ways people fake their own death, with one chapter about the Philippines where bodies can be bought and funerals staged for insurance fraud.

Both these books came to mind again earlier this year, with two events. In February, shortly before lockdown, the tech beat buzzed over a cyberlibel case filed by the founder of the notorious 8chan site, Fredrick Brennan, and its current owner, Jim Watkins; and in August, the Financial Times had a brief story on a Wirecard business partner, Christopher Bauer, being reported dead here in the Philippines; Bauer was the owner of PayEasy Solutions, one of Wirecard’s biggest sources of profit. 8chan had gained public notoriety during “Gamergate,” the 2014 online harassment campaign against women in the video game industry. The site, which hosts message boards, would come to feature in investigations into school shootings and hate crimes.

What all the stories had in common was the strange attractiveness of the Philippines as a haven for online criminal masterminds or the creators and owners of sites notorious for their right-wing extremism. Then in September last year, as part of the continuing feud among the past and present owners of 8chan, came another allegation: Jim Watkins, said Fredrick Brennan, was also a central figure in QAnon, the shadowy, extremist, conspiracy theory-focused network that has already elected members of Congress and, most recently, is among the groups suspected of having organized, and led, the assault on the US Congress.

The Asia Sentinel situated the Philippines in the “new wave” of organized crime in Southeast Asia this way recently:

As Asia Sentinel reported in April, transnational organized crime in Southeast Asia, driven by artificial intelligence, stablecoins, and blockchain networks, is evolving faster than at any previous point in history and expanding across the globe. Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and the Philippines were particular target sites picked by scammers to base their operations.

As law enforcement has cracked down, the scammers move to new countries with lax enforcement and malleable officials. These criminal networks are increasingly taking on the guise of supposedly respectable industrial and science and technology parks as well as casinos and hotels, investigators say, employing hundreds of thousands of multilingual complicit individuals as well as trafficked victims, rapidly enabling Asian crime syndicates to broaden the scope of fraud victims being targeted globally and exacerbating existing challenges faced by law enforcement.

The human cost is dire. See this 2024 BBC story: Hundreds rescued from love scam centre in the Philippines.

The Philippines had a cameo in another story, as the BBC reported in 2021, The Lazarus heist: How North Korea almost pulled off a billion-dollar hack:

And the hackers had another trick up their sleeve to buy even more time. Once they had transferred the money out of the Fed, they needed to send it somewhere. So they wired it to accounts they'd set up in Manila, the capital of the Philippines. And in 2016, Monday 8 February was the first day of the Lunar New Year, a national holiday across Asia.

By exploiting time differences between Bangladesh, New York and the Philippines, the hackers had engineered a clear five-day run to get the money away.

A. The POGO phenomenon: local vice, national addiction

Back in 2024 I summarized my views in this manner:

For years now I’ve been suggesting that the political interests and thus, activities, of the People’s Republic of China should not be confused with the political and social clout of Pogos who exist in defiance of the Chinese government. The Pogos are, arguably, stronger: Beijing’s requests verging on orders, to Manila, for a crackdown on Pogos never resulted in anything more than cosmetic “busy-busihan” as money talks and Pogos have lavished funds on our upper, middle, and political classes; and since all politics is local, the easygoing spending of Pogos makes them more valuable than presidential patronage or foreign affairs. Investigations so far have been racist in their lazy assumptions and breezy unwillingness to take into account the messy state of the documentation of many Filipinos, the different subgroups among Chinese Filipinos, and differences between Pogos’ and Beijing’s efforts to influence officialdom.

Just the other day, the Washington Post came out with this special report: Chinese association accused of mixing crime and patriotism as it serves Beijing:

The Hongmen network is under active investigation by law enforcement in Malaysia for alleged involvement in financial crimes, including fraud, bribery, stock manipulation and money laundering, and in an espionage case in the Philippines, according to officials who confirmed probes that have not been previously reported.

B. eSabong: Some sinister got hatched

Here’s the story thus far, Dead Water: The hidden graveyard beneath Taal":

Between 2021 and 2022, 34 individuals associated with sabong were reported missing in separate incidents across Luzon. While the cases initially drew public and media attention, sustained investigation efforts declined over time. No remains were located, no suspects were charged, and official updates became infrequent. The disappearances remained unresolved, with limited institutional follow-through and minimal public disclosure.

In June 2025, one of the detained suspects in the case filed a petition to qualify as a state witness and disclosed that the 34 missing individuals had allegedly been executed and their bodies submerged in Taal Lake—a volcanic caldera lake known for its geothermal activity and historically limited accessibility. The statement, if verified, reorients the investigation toward a forensic and environmental challenge previously unaccounted for in official efforts.

The statement brings attention to ongoing gaps in forensic capacity, potential criminal links, and the difficulty of maintaining institutional focus on unresolved cases…

The lake cited in the testimony is not the crater lake inside Volcano Island but Taal Lake — the larger volcanic caldera lake that surrounds it. Unlike the crater, which is highly acidic and inhospitable to life, Taal Lake is freshwater, supporting aquatic species such as tawilis and tilapia. Both swimming and fishing remain viable in its waters, despite its volcanic origin.

Despite sustaining aquatic life, Taal Lake presents acute forensic constraints. Its depth, geothermal flux, and sedimentary instability complicate postmortem recovery. Though not acidic like crater lakes, its thermal profile and microbial activity may hasten decomposition and obscure remains. A 2017 study on tropical volcanic lakes suggests such conditions hinder long-term retrieval, rendering clean recovery increasingly improbable over time.

In Filipino oral tradition, volcanic lakes are viewed as symbolic boundaries, places associated with disappearance and transformation. Anthropologist Nicanor Tiongson refers to them as gates, where what enters may not return as it was. The use of Taal Lake, in this case, holds both practical and cultural implications…

Understanding how the disappearances occurred requires examining what sabong had become, an informal, high-volume industry with limited oversight and growing ties to organized operations.

By 2021, e-sabong, the digital offshoot of traditional cockfighting, had grown into a ₱640-million-per-month industry, based on figures from PAGCOR. Its expansion was driven by pandemic lockdowns and the rise of mobile betting, but in the absence of effective regulation, it became vulnerable to exploitation by criminal groups.

Criminal networks allegedly used the platforms for money laundering and consolidation of influence… Philippine Center of Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) reported financial links between e-sabong firms and members of political dynasties, pointing to blurred lines between regulation and vested interest.

The missing sabungeros were not casual participants but informal workers: runners, handlers, and small-scale bettors embedded in an unregulated economy. Their roles became expendable once they posed legal or financial risks. By the time e-sabong was suspended in 2022, much of the harm had already taken root.

Disappearance emerged as a means of enforcement, sustained by institutional gaps. Impunity, in this context, was not incidental; it reflected structural conditions that allowed it to persist.

As an Inquirer editorial put it,

To this day, not a trace of the men has been found since they were allegedly killed for running a game-fixing racket that angered big-time e-sabong operators. For all the notoriety of crime-infested Pogo hubs, these don’t quite come close to the series of incidents that spelled the doom of e-sabong even during the gambling-friendly days of the Duterte administration—what Justice Secretary Jesus Crispin Remulla described in February as the “mass murder of people.”

Front and center in this story is someone who’s gotten administrations into hot water. The Secretary of Justice is now spooked by the extent of what’s being uncovered:

Remulla said intelligence reports suggest that the elusive mastermind behind the disappearances claimed he could even influence the Supreme Court…

While withholding the identities involved, Remulla revealed that the suspected mastermind belongs to a group of around 20 individuals—some of whom are said to be current or former government and police officials—who have adopted a “corporate setup” to run the multibillion-peso e-sabong industry.

By way of background there’s this industry-specific overview, see E-Sabong: The Rise And Fall Of The Deadly Betting Craze In The Philippines:

It was a pandemic-era betting craze that contributed enormously to the Philippine economy throughout COVID-19.

But e-sabong – where players watch and bet on cockfighting via online platforms – came at an enormous cost to the country’s citizens.

At the height of the e-sabong craze, levels of crime rose drastically, with all members of society – including police officers – looking for a means of paying off their rapidly accumulating debts.

Robberies, abductions, and even suspected murders were all reported as occurring because of the widespread addiction to e-sabong.

Despite these terrible social impacts, e-sabong’s rise was rapid, and its fall excruciatingly slow.

This being thanks to high-flying gambling tycoons, immense government tax profits, and a President who failed to see e-sabong’s social impact until it was almost too late

As this 2021 story put it,

[S]ays Lambert Lopez, chief financial operator of Sabong International (SI), the online cockfighting platform of Negros-based Visayas Cockers Club[:]

“Actually, it takes a village to run it,” he shares. “We do live video streaming coverage from our arena studios transmitted via a dedicated, secure broadband connection. Then we direct the coverage to a website hosted on cloud servers. Inside the cloud servers is the proprietary game programming made by SI’s highly skilled developers. As for online marketing, we employ mobile technology making the platform very easy, convenient and fun to play.”

A 2022 news item on a Senate hearing put the immense amount of money generated by online cockfighting betting in stark terms:

The government generates a P640-million revenue from e-sabong operations in the country per month, a “pittance” compared to the P3 billion gross monthly income being earned by the online sabong firm of gaming consultant Atong Ang.

This came out during the hearing on Friday of the Senate public order committee which had Ang as resource person in connection with the disappearance of 31 cockfight aficionados recently.

Ang was asked by Senate Minority Leader Franklin Drilon regarding the amount of bets coming in in his company’s daily operations.

According to Ang, daily bets total to an average of P1 billion or P2 billion. “More or less P60 billion po a month,” he added.

Of this P60 billion worth of monthly bets, Ang said they get five percent or P3 billion a month.

Ang noted that their agents get P2 to 2.5 billion from this.

Obviously the take is worth fighting over. What Congress giveth, Congress taketh away. The old-fashioned but messy can be sanitized by being corporatized, firming up the principle that gambling is a government monopoly. Iris Gonzales lays out the numbers:

Now, just like e-sabong, the e-games sector, which offers a wider spectrum of games – including just about everything in brick-and-mortar casinos, plus the well-loved bingo – has seen a phenomenal increase in revenue in 2024 alone, growing by 464.38 percent to P35.71 billion in the third quarter of last year from just P6.32 billion in the third quarter of 2023.

For the whole of 2024, PAGCOR expects e-games revenue to have hit P100 billion.

On the other hand, during the third quarter of the year, revenues from licensed casinos declined by 2.27 percent to reach P50.72 billion.

Revenues from PAGCOR-owned games under the Casino Filipino brand fell by 26 percent to P3.64 billion as more players shifted to online platforms.

Imagine that.

C. Add “pig-butchering” to your criminal lexicon

This is the story that kicked off this issue of our newsletter: the Asia Sentinel’s US Busts Philippine 'Pig-Butchering' Op":

Investigators identified at least 430 suspected victims in Texas, Arizona, Virginia, Iowa, California and other areas who fell for so-called “pig-butchering” schemes, a translated from Chinese shāzhūpán and which refers to a scam in which the victim is “fattened up prior to slaughter,” encouraged to make increasing financial contributions over a long period in fake investment schemes, usually in cryptocurrencies…

Additional Readings

By way of background on the traditional manifestations of gambling, these readings are both interesting and helpful: from the most ancient to the newest of the traditional forms, there’s:

cockfighting: see History and General Background of Sabong in the Philippines by Ateneo students David Agcaoili, Carl Chingkoe, Charles Cuerpo, Jodi Diomampo, Althea Yu.

jueteng (in the 1930s jargon our papers love, the “numbers racket” or “numbers game”): see also, Randy David’s 2005 piece, Sociology of jueteng:

The daily take from this game runs into hundreds of millions of pesos. The bets are collected from poor people who gamble their last pesos for the tiny chance of hitting the pot. The bet collectors are a tight network of resourceful cadres that roam the communities at least twice a day, going down to the level of the household. This is a convertible system that is utilized for a variety of purposes depending on the need – monitor the political leanings of households, solicit or buy votes, distribute campaign leaflets, exchange foreign currency, remit OFW earnings to families, or even retail illegal drugs.

The tremendous profitability and illicit nature of the enterprise invite harassment and protection from those who are assigned to enforce the law. It is easy for the police and local authorities to turn a blind eye on jueteng because this form of gambling is generally viewed as a “victimless” offense. The bettors who lose their money do not feel exploited or injured. The fact that the government runs its own lottery and casinos virtually washes away the wrongness of the whole game.

Jueteng has its own rationality. There are few forms of illicit income in our culture that are as widely shared as the take from jueteng. Bet collectors or cobradores and their cabos, an assortment of individuals with little education or qualification for any other job, keep 15 centavos of every peso they collect. Policemen get an untaxed costof-living allowance from jueteng that is regularly added to their salary. Mayors, congressmen and governors are offered an allowance they can spend on their personal charities and vices, without having to account for it.

and Jai Alai: Until the postwar era cockfighting didn’t confer social prestige but the importation of this Basque sport before the War accomplished two things: it conferred social sheen on the sport, made it, by legislative franchise, the exclusive domain of the wealthy, but derived its financial luster from being a state monopoly on a new form of gambling. See The Jai Alai Building, a beautiful example of Art Deco in Asia.

There will come a time when how this all merges with drugs will have to be tackled. Two explorations by way of placeholders: The blueprint for the ‘War on Drugs’ and Lies, damned lies, and drug statistics.

This week’s The Long View:

The Long View

Throwing out assumptions

By: Manuel L. Quezon III – @inquirerdotnet

Philippine Daily Inquirer / 05:06 AM June 25, 2025

Writing in the Asia Sentinel, Khanh Vu Duc observed that even as United States President Donald Trump abruptly left the G7 Summit in Canada, Chinese President Xi Jinping had posted a message on X: “History doesn’t just repeat itself, it accelerates.” Just the day before, he posted: “The world can move on without the United States.” In the words of Duc, “Together, these two statements—brief, deliberate, and strategically timed—capture a growing perception: the world is learning to operate without American leadership, not in hostility but in adaptation.”

Trump had already proven himself the outlier at the summit, the threefold agenda of which was global tax coordination (particularly the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development-backed plan for a global minimum corporate tax rate), climate finance, and long-term military aid for Ukraine. With Trump out of the way, the remaining leaders went ahead.

And this, Duc argues, is the point Xi Jinping was making: “As America steps back, China positions itself not merely as an alternative, but as the inevitable heir to global centrality. While Washington debates, Beijing narrates. With just a few words, Xi reframed the G7’s drama into a broader historical arc: the end of US dominance as a fait accompli.”

But the nation that dominated the headlines was America. There was the “will he” or “won’t he” speculation that finally gave way to the announcement that American bombs had been dropped on Iran’s most secure nuclear facilities. As Bill Bishop in his well-regarded newsletter Sinocism pointed out, “The Xi administration was relegated to a powerless observer in this conflict, probably angered the Iranian leadership with its lack of assistance, and now will find whatever angle it can to criticize the US. But I think they will be relieved the Iranian response to the US bombing was performative, the Straits of Hormuz remain open, and the risk of a wider war may be abating.”

The Australian defense analyst Hugh White recently published an extended essay arguing that even as people ask whether America will concede Asia to China, the fact is that it already has: to be precise, as Arnaud Bertrand helpfully paraphrases it, “withdrawal occurs when a great power loses the ability to impose its will in a region.” It works like this: “The test is simple: can America still compel regional actors—China specifically—to do things they don’t want to do or deter them from things they do want to do? When the answer becomes “no”—when China can safely ignore or defy American preferences—withdrawal has occurred regardless of how many bases remain.”

Bertrand, paraphrasing White, adds compulsion requires three things working together: “overwhelming economic leverage, decisive military superiority, and credible willingness to escalate to nuclear war if necessary.” Absent one, it won’t work.

But what happened in Iran—with the added news of both Israel and Iran accepting a ceasefire brokered, it seems, by Washington—challenges the assumptions outlined above.

The Israeli analyst Haviv Rettig Gur argues the American bombing of Iran is a demonstration of what he calls the “Trump Doctrine,” which, according to him means “Trump’s brand of isolationism shows the United States can still secure the world, protect the world, and police the world, without having to secure, protect, and police it; and the basic idea is the ally does the heavy lifting, and the United States comes in to deliver the coup de grace.”

This addresses both the assertions of American military decline and the perennial question that haunts all American allies (as Hugh White put it, “Can we depend on our allies?”) as Rettig Gur says, “To my Taiwanese friends and South Korean friends, and Japanese friends, and European friends, you face enemies and you face an America that doesn’t want to fight for you: it will fight for you if you can fight for yourself; that’s the point, and I want to tell you that it has always been thus.”

Returning to Duc, he asked, “Xi offered one version of the future: a world where power migrates from the careless to the prepared. Trump, perhaps unintentionally, reinforced that narrative. But Carney, the G7+, and the broader community of democratic nations offered another path: a recalibrated, post-American leadership model rooted in shared purpose and mutual respect. The world is moving. The only question that remains is: Who has the vision, credibility, and courage to shape where it goes?”