By way of preamble, these were my thoughts on Facebook last June 6, where I sorted out my thoughts prior to my column and today’s commentary:

Quick notes on the looming constitutional crisis on impeachment, the Senate, and the presidency:

1. The midterm as referendum produced a hung jury: the main contenders ended up in a draw, not least because both sides had weak slates (and, in fact, for the first time ever, neither side had a full slate: the administration by attrition, the Dutertes because they lacked the means to put together a full slate in the first place). The administration could not harness its strengths because of the economy pulling down the president's standing and thus, the attractiveness of his slate, which never came up with a cohesive fighting message; the Dutertes because they themselves are divided and the erosion in their alliances after leaving office.

2. What tipped the balance are Aquino and Pangilinan: this is not the place to explain the dynamics of their victory but suffice it to say they benefited from two main contending slates, the unwillingness or inability of the public to vote full slates, their own prudent tactic of declining to frontally attack either side, some historical advantages (a story has to be written how the Aquinos are champion campaign managers: Benigno Sr. prewar, Paul Aquino post-EDSA) and a shift in the Iglesia in not just anointing expected winners but rather limiting their demand for national support to only two candidates in exchange for local support, etc. This tipping of the balance meant the overall message of the midterm was anti-administration (but neither was it entirely pro-Duterte).

3. Everyone seems convinced the lesson of the midterm is something it wasn't --the Dutertes believe they were validated and are stronger (see map showing national vote for them down, though Mindanao has remained theirs)-- the Middle Forces (Yellow, Pink, SocDem, etc.) think they are stronger rather than having benefited from administration and other command votes and the weakness of the other slates-- the public seems to think the administration is more defeated than it was.

4. The real question is whether the enterprise threat of the Dutertes is being met with a resolve to go for broke by the President. No signs or portents he is leading the fight or betting the farm. This means no one is sticking their neck out (if he isn't, why should anyone else). It also means there is an eerie silence on whether their is anyone marshaling the offense/defense for impeachment. While the President is hewing close to traditional expectations of pious hypocrisy --everyone knows it's insincere but in our society, it's important to go through the motions -- by denying interest in impeachment (probably truthfully: there was another way to skin this cat but the Speaker had his own ideas), it has to be supported by someone being the point person to deal with the Senate.

5. It's this doubt or uncertaintly that has infected everyone, the Senate included. The hung jury results means no one knows how an impeachment would turn out. So how can anyone make a safe bet? Because an unsafe bet is dangerous.

6. Hence we are in the era of trial balloons. The Dutertes cannot risk an actual trial; they have to leverage the perception they are stronger than they are, by stopping things getting to the point of mounting a trial. Are they really strong? Float the idea of a resolution: see how people reacts. Until it becomes clear, establish a holding pattern: just debate things to death until one or more things are resolved:

a) The 19th Congress peters out and expires, kicking the problem to the 20th Congress

b) The Supreme Court forces the Senate to do what it is expected to do

c) Public opinion shows who really has public backing, helping to decide the leadership contest --until that happens, the leadership contest is such that the Duterte bloc is important and necessary to attract

d) the President shows signs of decisiveness or an indicates how willing he is to make any deal necessary to achieve an outcome

7. So we have until the convening of the 20th Congress and that includes organizing the chamber and the President's SONA: lest we forget, this was the actual schedule Escudero wanted in the first place because it's the politically safest one for all the senators.

8. Again until then it's anybody's game which is why the different trial balloons are being launched. It is interesting that his election and post-election behavior suggests the only one in the Duterte side of the fence thinking a long game is Bong Go: he is establishing his own bailiwick, he has distanced himself from the Bato resolution, he can be the last man standing if (as it's entirely possible) Marcos-Duterte remain in a battle of attrition with neither side capable of toppling the other all the way to 2028.

9. The Comelec's swift elimination of Duterte Youth shows the levers are firmly in the hands of the admin; the Cabinet reshuffle, modest as it was, eliminated the most obviously divided in their loyalties. It's minimal extent, by the way, also means the President isn't as beholden to the Commission on Appointments, which would have compounded the costs of coming battles involving counting votes in the legislature.

10. The one thing that created the Senate and has been the obsession of every senator since its foundation is public opinion. The next month will show where it lies and to what extent the public cares. This, combined with whether people reach the conclusion (or not) that the President has the intestinal fortitude for a fight to the finish, or is simply content to pack his bags again for exile in 2028, will determine what the Senate does.

My commentary in the Asia Sentinel:

Crisis of Paralysis in Manila

Mixed signals from the public and the president leave the Senate risking a constitutional crisis

Jun 09, 2025

By: Manuel L. Quezon III

What three people did following the Philippines’ May 3 midterm polls suggests that the leadership knows what’s what, and it’s this: with no clear outcome midterms, the warring President Ferdinand Marcos Jr, his terminally estranged Vice- President Sara Duterte, and the Senate President Francis Escudero are all stymied, one way or another, as they all confront unfinished business from before the elections: the impeachment trial of the vice-president.

The midterms were supposed to boost one side and diminish the other; instead, all sides are left unsure of where they stand. The result was a draw. The Marcos and Duterte coalitions elected five candidates each of a maximum of 12. What confused matters as far as both the political class and the public were concerned was the election of two more who represent the center-left forces that the Dutertes and Marcoses have tried to eliminate politically since 2016: one is a scion of the Aquinos and the other, the defeated vice-presidential standard bearer of that coalition in 2022.

The President, after announcing he was asking appointed officials, starting with his Cabinet for their “courtesy resignations,” ended up engaging in a minor reshuffle which essentially concentrated on removing the vestiges of his political accommodation with the Dutertes from his Cabinet. The Vice President, for her part, engaged in preventative rhetoric by vowing “a bloodbath” if her impeachment trial proceeds. And the Senate President picked up where he’d left off prior to the election: responding to the Philippine constitutional instruction that upon receipt of articles of impeachment, the chamber he leads is to proceed with a trial “forthwith,” by dragging his feet.

Only in the Philippines can the obvious be debated as if what has long and widely understood is suddenly newfangled and unknown. Impeachment has been in every constitution for nearly a century. Having been borrowed from the Americans, there is ample philosophical and legal precedent to address any question that might arise. The question being debated is this: can an impeachment passed by the House in the 19th Congress (which expires on June 30, 2025) be tried into the 20th Congress (which convenes on July 1, 2025), or must all the proceedings be finished before July?

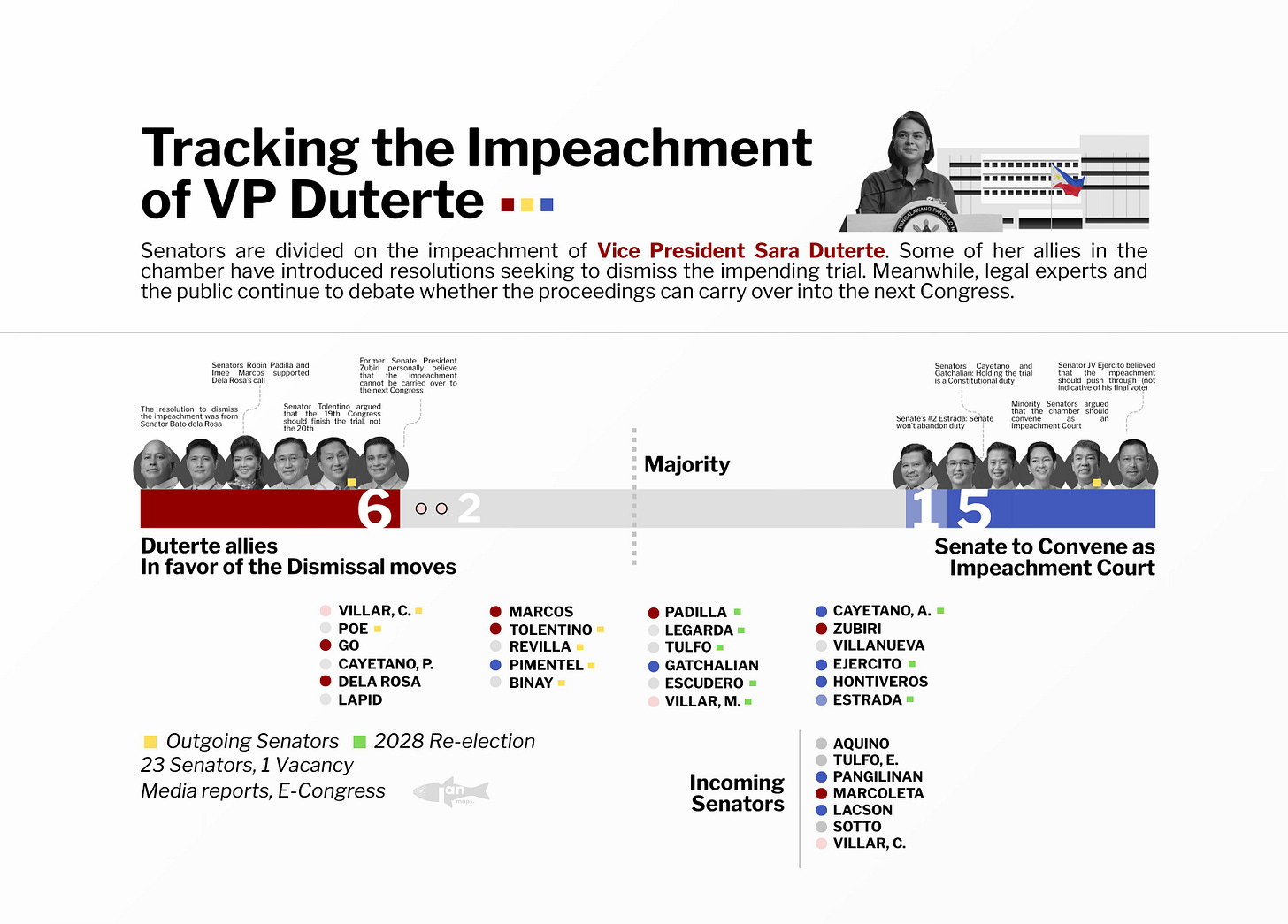

With the enthusiasm of medieval monks debating how many angels can dance on a pinhead, senators are debating—or, to be precise, speculating—on the topic even as irate civil society and educational institutions are suddenly exercising their atrophied activist muscles in outrage over the imbecility of the arguments. A resolution has been drafted by Senator Ronald dela Rosa, one of Duterte’s principal lieutenants, to dismiss the charges without bothering with a trial.

Complicating the issue is that it’s become tied to the first order of business of the incoming 20th Congress, which is the election of the officers of both chambers. The bloc identified with the Dutertes is a valuable commodity that neither of the two leading candidates—the incumbent Senate President, Francis Escudero, and a former Senate President, Vicente Sotto III, recently elected to an unprecedented fifth (nonconsecutive) term—can ignore.

Which explains the posturing of both Escudero and Sotto, who have taken to various (because ever-morphing) expressions of unease concerning the Duterte impeachment. Escudero, at the start, when the House delivered its articles of impeachment on the last session day before the election recess, had expressed the intention of mounting the trial in the 20th Congress, specifically only after President Marcos delivered his State of the Nation address in late July. He eventually had to backtrack and went through the motions of making minor preparations until he more recently said he would leave it up to the Senate as a whole to decide what to do. Sotto, for his part, says the rules are subject to interpretation, and besides, the mess is due to Escudero not getting the trial going earlier.

Here, President Marcos once more enters the scene. The election recess of Congress led to proposals that the President use his power to call Congress to a special session for the purpose of holding the impeachment trial in the midst of the campaign. It didn’t happen because the President said he’d do so if asked by the Senate and it didn’t.

Simply put, it made no sense to mount a trial in the midst of a campaign, when the impeachment itself had become a campaign issue due to the timing of its passage by the House. The problem is that the midterm failed to resolve what it was meant to resolve: the balance of power in the Senate going into the trial, itself an outcome of public opinion as expressed in the senatorial results, concerning the two main contending parties: the Marcos and Duterte coalitions.

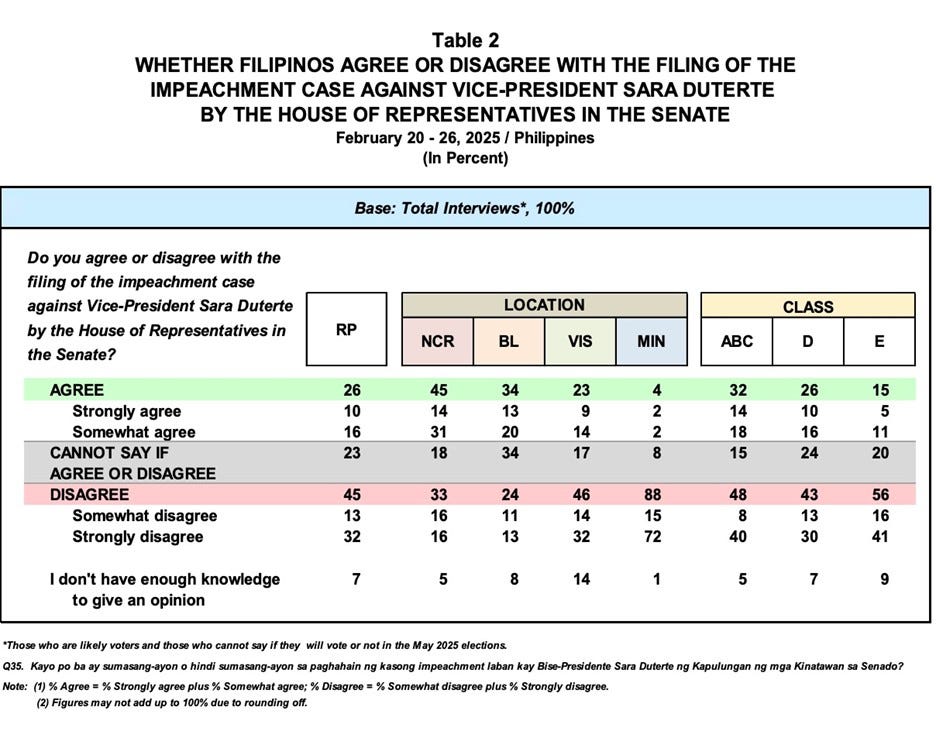

The Senators cannot coalesce because the verdict is unclear. In the case of tie, the burden is on the senators to sniff out for themselves, which way they think the wind is blowing in terms of divided public opinion.

Public opinion—fickle because emotional—has severely punished senators before when they misread the signs of the times in an impeachment. A whole roster of formidable veteran senators found their careers extinguished outright or handicapped for a decade because they bucked public opinion and procedurally supported embattled President Joseph Ejercito Estrada during a crucial vote on evidence during his impeachment trial. The result was a walkout by the prosecution followed by rallies in the streets preceding the withdrawal of support by the gatekeeping institutions of Philippine democracy: the church, civil society, and the military, which toppled Estrada from power.

A Philippine senator summed up political prudence in this manner: “less talk, less mistake; no talk, no mistake.” The slower the Senate creeps to a trial, the less of a chance it will fatally alienate whichever part of the electorate turns out to matter; having no trial means there is no one to alienate as a result of a verdict. The Dutertes do not want a trial at all, because evidence has a peculiar ability to foment public outrage. Senators about to leave office and those about to enter office do not want a point of no return so late, or so early, in their terms, as the case may be.

Yet again, we return to President Marcos. Time and again, he has said he didn’t want an impeachment. He has even gone so far as to publicly desire reconciliation with the Dutertes who, after all, were the ones who began hostilities. In either case, whether he is sincere or not is not the point; in a society where appearances arguably matter more than substance, it is expected of presidents to frown on any move that can cause disorder, and it is equally expected of presidents to be the first to offer an olive branch to foes. This performative aspect of the job has been satisfied and the politically-desirable answers obtained, when the Senate bogged down in intramurals on impeachment while it was Duterte who vowed a bloodbath and insultingly responded to the proffering of reconciliation –the troublemaker isn’t in the Palace.

Meanwhile, the President-as-thoroughbred knows his own political class well enough to trim down opportunities for extortion (or haggling) on the part of senators or congressmen, both of whom comprise the Commission on Appointments that must confirm or reject his new cabinet appointments. After all, the expected motions in the wake of a midterm defeat have already been made: the ritual acceptance of the popular will; offering up human sacrifices as atonement by purging the Cabinet, however lightly.

But this is not the time to expand the opportunities for horse-trading considering the conventional wisdom that an impeachment trial is one-third about the evidence (making for the strength or weakness of the case), one third-about presentation (which affects public opinion), and a third about management (however defined: often in terms of maintaining discipline or overcoming scruples).

When President Benigno S. Aquino III led the charge to impeach and convict then-Chief Justice Renato Corona, aside from the president himself taking the lead to make the case before the bar of public opinion, it was widely understood in political circles that he had two behind-the-scenes managers for the effort: Florencio Abad, who was Secretary of the Budget, and Manuel Roxas II, who was a principal lieutenant and party grandee. Marcos has taken an altogether different tack as noted above: he remains publicly above the fray. There is no sign, either, that there is anyone serving as an emissary between the Senate and the Palace: and so, to the ultimate question of just to what extent, is Marcos prepared to bet the farm, there are no signs or portents that anyone can point to.

These leave the Senate all the more isolated; it must consider bearing public opprobrium without any guarantee they will make the right bet or even receive any support, explicit or implied, from the party most aggrieved by the Dutertes –the Marcoses.

It is entirely possible that there is an impeachment manager, and that Marcos is truly keeping his cards close to his chest. It is just as possible that he has not decided if this is a battle he is willing to bet the farm on, at least not yet. He could be in the same boat as the senators: with public opinion divided, the month between the expiration of the current congress and the start of the term of the next, is a time for wheeling, dealing, and gauging public opinion by means of trial balloons –of which, as we’ve seen, there are plenty.

An impatient House of Representatives, egged on by an equally impatient civil society (enjoying the flexing of its atrophied muscles), just might relieve everyone of the burden of guessing where public opinion lies, by asking the Supreme Court to intervene by ruling on whether an impeachment trial can straddle two congresses. Senators, including those vying to be the next Senate President, can then say the Supreme Court has tied their hands.

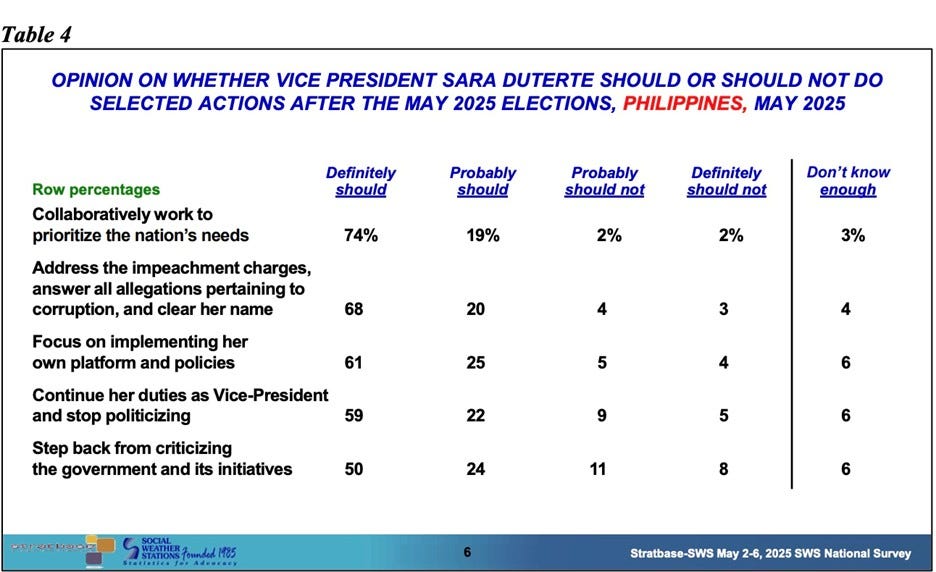

Then the trial would proceed, but it wouldn’t just be the Vice-President in the dock: the Senate would be on trial too, since the public has expressed skepticism about its impartiality even as it expects the process to unfold and a verdict to be reached on the merits.

But even without the Supreme Court being asked to weigh in, civil society which has been feeling empowered by the controversy, is increasingly being joined by other groups previously discounted as consequential in the post-Duterte era: manifestos have been flying thick and fast as political and social groups and even the voices of some Catholic figures of influence, have embarked on organizing for a series of prayer vigils and rally to pressure the Senate to make up its mind.

This is tied to that feeling of renewed relevance and strategic importance that the formerly defeated and disillusioned center-left forces have felt in the wake of the surprise election of two of their candidates to the Senate. They simply refuse to concede the field to the Dutertes, are impatient (and generally hostile) to the Marcoses, believe in accountability, and actually have individual and collective experience with impeachments. Whether they can mobilize in numbers that can impress, and maintain the pressure so as to keep the issues front and center and thus, top of mind, is the kick-off to the month ahead that will determine the fate of impeachment.

That more senators are going on the record that institutionally, they have no choice but to proceed with an impeachment trial, suggests where public opinion stands is getting clearer to them. The longer it takes for the Duterte bloc to fail to reach a majority consensus to junk the trial, the more those still on the fence will be emboldened to take the popular path of seeing where a trial leads.

A resolution by July might then be possible, with the President having kept his powder dry by keeping everyone guessing how committed he is to any particular outcome, and without having to invite an intervention by the Supreme Court.

Manuel L. Quezon III is a Filipino writer, former television host, and grandson of former Philippine president Manuel L. Quezon

Last week’s The Long View:

The Long View

Hot camotes

By: Manuel L. Quezon III – @inquirerdotnet

Philippine Daily Inquirer / 05:06 AM June 04, 2025

Since timing is everything, three people got us to where we are. The first was the Speaker of the House, who decided to impeach the Vice President just as Congress was preparing to go on recess for the midterm elections. The second was the President, who declined to call Congress into a special session during the election break for the purpose of holding the impeachment trial during the campaign period. The third was the Senate President, who planted himself firmly in the ground like a camote and decided to do the bare minimum with regard to impeachment.

A review of Paolo S. Tamase’s “Emerging Issues in Philippine Impeachment and the Accountability Constitution,” his summary of a forum on the topic last February, is helpful in outlining the three dilemmas confronting senators as the 19th Congress limps toward extinction this month while waiting for the 20th Congress to be born next month. The first two were resolved through inaction: whether the Senate, could on its own, conduct an impeachment trial while Congress was in recess, or, whether the President, by issuing a proclamation calling Congress into special session, could enable an impeachment trial to proceed—both became moot and academic.

A third dilemma, however, remains: as one Congress bows out and another convenes, can an impeachment trial proceed? The answer depends on whether the Senate can be considered a continuing body. If you ask the Americans after whom we patterned our Congress and its powers, the answer is a definite yes: impeachment started in an old Congress and continues in the new one. Filipinos who can’t leave well enough alone will try to argue things to death, including hedging by insisting the Senate might, and it can, but only if the senators in the new Congress decide to do so—the choice is theirs. Of course, there are others who will argue the charges will expire when the current House bows out by the end of the month.

To be fair, there wouldn’t even be a debate on whether the Senate is a continuing body if only the losers of pre-martial law hadn’t tried to improve their chances for senatorial election, by making the post-1987 Senate elect half its members every six years, instead of a third every three years, which is what the pre-1973 Senate (which was indubitably a continuing body because at any given time, fully two-thirds of its members were in office, constituting a majority to do business) used to do. Electing 12 at a time gave those who lost out by coming in ninth and below in the old days, a chance to make it (and also inadvertently created the demand for votes, which dagdag-bawas was meant to supply, because while the system changed, the behavior of voters remarkably remained the same. To this day, voters find it easy to decide on eight senators but tough to do so for more!).

But today’s situation began because of the Senate President being politically stingy. So economical in action was he, that when he defended his inaction, he did so by leaving out mention of the word “forthwith”—that constitutional command that made his making like a camote controversial in the first place.

With the election over, the public didn’t help matters by turning out to be a hung jury: its referendum on the sitting president resulted in a 5-5 tie between Marcos and Duterte, The two pink candidates tipped the balance against Marcos, but neither of the two could be considered an endorsement of Duterte. With no clear public signal, the Senate President boldly decided to double down on that sweet ole camote style.

“We cannot bind the hands of the next Congress,” he droned on in the kind of statement a Senate president makes when he doesn’t expect to be head of the chamber when it reconvenes. The leading candidate to replace him, the once and future Senate President Vicente Sotto III, is doing his part to prove that yes, the camote can—meaning he can be every bit a camote as his soon-to-be predecessor, by declaring that he thinks an impeachment passed in the 19th Congress ends where the 20th Congress begins.

The older generation that cringes whenever Francis Escudero presides over the Senate, wearing what appeared to be either a polo barong or one with the sleeves rolled up so high as to imitate one, might prefer to replace the man smirking at the rostrum with a comedian capable of being suave and polished during office hours. But that is to substitute the ridiculous with the absurd—as both seem to be more interested in proving which camote can be Senate President again than in fulfilling the obligation to render judgment on the charges already on the record because transmitted to and accepted by the Senate for trial.