Midterms and Courtesy Resignations

What happens when presidents invoke traditions the public no longer recall

This week’s column takes off from The Philippines’ Midterm Massacre and The four horsemen of the apocalypse in which I looked at the surprising midterm results for 2025. The verdict —a mixed but in the end, negative one— having been handed down, it was incumbent on the President to show he got the message. He did so in two ways: he reiterated he’d never wanted an impeachment (likely a true statement: there’s more than enough evidence to nail the Veep by other means, it’s said, due to their spectacularly blithe handling of confidential and other funds) which underscores his wanting to maintain order, and he engaged in the time-honored tactic of mounting a sweeping reorganization of his Cabinet by asking everyone to submit their courtesy resignations to give him a free hand.

The surprising thing is how it came across as something that’s never done before, which is is only true if your frame of reference doesn’t even go back twenty years to when Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, herself hewing to old presidential traditions, did the same thing and much for the same reason, a midterm defeat.

That defeat, incidentally, remains contested in its depth and reasons for taking place; in Midterms decided at the start I argued a fundamental distortion in the midterm-as-referendum tradition (and expectation) is that both of the main antagonists couldn’t form full slates (uniquely so in the case of the administration). That, and in The passing of opportunity I observed there was more weakness to the Duterte efforts than is usually conceded. Much earlier, in Old rules no longer apply I’d pointed out both antagonists seemed to think media still played a role in forming public opinion it no longer does.

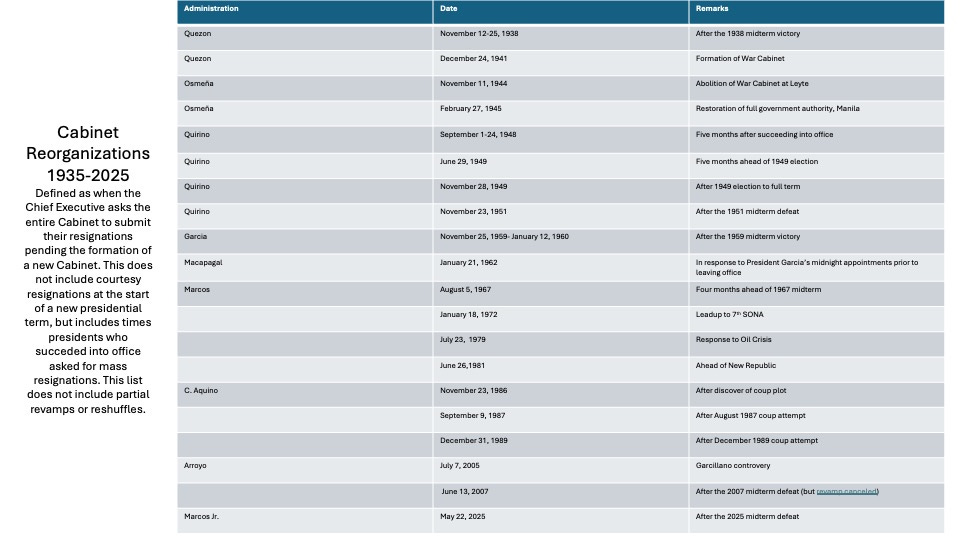

Here’s two sets of data I found useful in preparing my columns.

This week’s The Long View

The Long View

The ghosts of past purges

By: Manuel L. Quezon III - @inquirerdotnet

Philippine Daily Inquirer / 04:30 AM May 28, 2025

Of the three restoration regimes we’ve had—Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, Benigno Aquino III, and Ferdinand Marcos Jr. —what sets them apart from their post-Edsa presidential contemporaries is a longer institutional memory, so to speak, of the presidency. In the case of Arroyo and Marcos, that memory is much longer than that of Aquino, who bore his mother’s administration constantly in mind. In the case of Arroyo, it included a longer stretch of time encompassing the second half of the Third Republic.

I’d even go so far as to argue that this longer memory meant that these presidents instinctively sought to invoke precedents that were politically normal during the pre-martial law era, but which are essentially forgotten both by their political peers and the media, which reports on and interprets the political actions of presidents.

Consider Mr. Marcos’ decision to ask for the courtesy resignations of his entire Cabinet and other presidential appointees. The terms used were contemporary—a “bold reset”—though the language of the President was in keeping with that of his predecessors stretching back to the time of his father and long before: “The people have spoken, and they expect results.”

We forget after a midterm that it’s traditional for presidents to have a Cabinet revamp: when rebuked by a defeat, throwing people overboard offers a human sacrifice to the public; where presidents do well and feel validated, it pays off old debts.

The last to have a revamp like this happened to be Arroyo. But then, 2007 was nearly two decades ago, and in terms of reporters alone, the few who still have jobs were mostly too young to remember even her presidency.

Let’s be specific: We’re talking about an extraordinary act and one widely understood to be such, defined as when the Chief Executive asks the entire Cabinet to submit their resignations pending the formation of a new Cabinet and not the usual revamp or reshuffle involving a few, part of the normal course of business.

A quick review suggests this roster, 1935-2025. For the first nationally elected administration, Manuel Quezon, it happened twice: from Nov. 12 to 25, 1938, after the 1938 midterm victory (the only 100 percent victory until Rodrigo Duterte’s 2019 midterm sweep), and Dec. 24, 1941 for the extraordinary need to abolish and merge departments and form the Commonwealth War Cabinet. Sergio Osmeña, twice: on Nov. 11, 1944, after his return to Leyte and on Feb. 27, 1945, in Manila, when the full authority of the Commonwealth was restored. For his part, Manuel Roxas was authorized to reorganize the government but didn’t mount a total revamp.

Elpidio Quirino, however, undertook a total revamp four times: although the Roxas Cabinet submitted their collective resignation when he assumed office, he declined to accept it, and Quirino didn’t ask for courtesy resignations until Sept. 1 to 24, 1948, or five months after succeeding into office and again on June 29, 1949, five months ahead of the 1949 presidential election. He did so again on Nov. 28, 1949, when the results of that election became known; and finally on Nov. 23, 1951, after the disastrous midterm defeat.

Most entertaining was Carlos P. Garcia’s after his 1959 midterm victory: it stretched at the very least from Nov. 25, 1959, to Jan. 12, 1960, including, at first, broad hints (after his initial request for courtesy resignations) for officials to comply, and what seemed like nagging every few weeks. Diosdado Macapagal’s was different: he asked for mass resignations on Jan. 21, 1962, just a few weeks after assuming office, upon the advice of Justice Secretary Jose W. Diokno in response to Garcia’s packing the government with midnight appointees.

Ferdinand Marcos Sr. did mass layoffs four times: on Aug. 5, 1967, four months ahead of the 1967 midterms; on Jan. 18, 1972, in the lead-up to his 7th Sona; on July 23, 1979, in response to the oil crisis; and on June 26, 1981, a few days before he proclaimed the “New” or Fourth, Republic.

Former president Corazon Aquino called for mass resignations thrice, each after surviving a challenge to our newly restored democracy: on Nov. 23, 1986, when the “God Save the Queen” plot was uncovered; and on Sept. 9, 1987, and Dec. 31, 1989, after surviving coup attempts. Arroyo did so twice: on July 7, 2005, in the wake of the Garcillano controversy and on June 13, 2007, after her midterm defeat –except, uniquely, after having asked for courtesy resignations, the Palace ended up backtracking and, uniquely, abandoned the scheme. Not until May 22 of this year, would another president, Marcos Jr., again ask his Cabinet and other appointed officials to submit their courtesy resignations.

Last week’s The Long View

The Long View

Outsmarted by AI

By: Manuel L. Quezon III - @inquirerdotnet

Philippine Daily Inquirer / 05:06 AM May 21, 2025

A heated debate is taking place within writerly circles. The question is whether the essays coming from a Facebook account—including one that caught my attention on the middle class in our country—are the works of a writer or created using artificial intelligence (AI). There is a generational aspect to the debate, with some senior worthies vouching for the existence—and skill—of the publisher and others contesting the pieces. As one Facebook commenter naughtily put it (about the piece on the middle class): “It’s being shared and praised by all the people judging writing competitions.”

Whichever side you might be on, the debate itself tells us the era of AI as a novelty is passing. If many are susceptible to thinking something produced by AI isn’t an original human work, there are also enough humans able to detect the telltale signs of AI-sourced material who can mimic the prompts required to produce something similar, or know the software to use to tell the difference. But there are obviously more who have access to AI than those who have access to the software to detect its use.

If we have seen public discourse—and even social stability—crumble because of a form of AI algorithms that tailor what we see to the kinds of things we like, to the exclusion of other views and ideas, then substituting machine-made written “works” for essays and comments is leading to: on one hand, machines talking to other machines, creating ripples as a result that affect what humans decide to consume or share; on the other hand, substituting AI for the human mind, while moving humans to embrace the outcome on the assumption they’re brilliant (because likable, agreeable).

One thing is certain. AI is not about tinkering with it to boil down boring reports, draft outlines (or even, as some have claimed to be able to prove, “write” official statements on behalf of at least one highly positioned elected official in the land), or create amusing images in the style of well-known artists; it’s already disrupting lives.

Among educators, a constant topic of discussion is the impact of AI on the output of students. It has become particularly problematic in terms of students passing off AI-produced items as their own original work. Some schools invest in software to detect this kind of fraud, and teachers view this sort of misuse of AI as a serious offense. At the same time, the pressure is intense for students to use AI, and not all schools invest in creating their own AI applications to provide a more structured, “safe” space for students to learn how to use AI without misusing it.

And to think the next step in a student’s life after graduation is almost certainly going to be decided by AI: their CVs, after all, are increasingly written using AI to more effectively meet the standards of AI (consider the wide use of ATS (Applicant Tracking Systems) in the private sector to go through the tedious process of sifting through applications).

Just yesterday, Aneesh Raman, chief economic opportunity officer at LinkedIn, had an op-ed in the New York Times, warning that AI “poses a real threat to a substantial number of the jobs that normally serve as the first step for each new generation of young workers.” The first disruption is being felt in technology. What is the future of a programmer when coding can increasingly be done through AI? But Raman says it will “play out in fields like finance, travel, food, and professional service, too.” Already, I hear lawyers worrying about entry-level tasks, such as contracts or even research, that can be done with AI. Though even here, as in academic use of AI (where AI is still liable to create sources when none can be found online), the clear limits of AI eventually being overcome, is simply a matter of time.

Even before AI as we know it today came to be, the idea of attaching data to individuals, to partially (if not fully) automate what used to be strictly human-centered and thus liable to be subjective, appreciation of another human for purposes such as loans, had already been perfected. The United States pioneered it but we are all familiar with it: the formulation of your credit score, which determines so many things about you, whether you get loans, or can obtain credit, and so on. China took this to the next level in what is euphemistically called its social credit system, which evaluates individuals and businesses based on their trustworthiness and compliance with laws and regulations: vast amounts of data collection through intensive mass surveillance are only possible today with advances in AI. Eventually, we will all carry electronic dossiers with us as we go through life, with a seamless connection between the different databases of the public and private sectors.

A vision of a profane future—not Our Father, but rather, Big Brother, who is not in Heaven but who is everywhere and nowhere in the Cloud—is what inspired the new Pope Leo XIV to take on the name of his predecessor, who confronted the evils of Marxism in the 19th century and whom, in the 21st century, this new pontiff believes humanity is called to confront: artificial intelligence.