Submarine cables: An undeclared war

You can connect to China or America but not both, as undersea cable battlelines are drawn

Last week I talked about the microchip rivalry between the US and China. Since my column and newsletter came out, Korea after initial unease, has increasingly solidified its commitment to this chip alliance with the US and Japan: on Monday, after years of hostility, Tokyo and Seoul recommitted to cooperation and the resumption of visits between leaders.

(An interesting read that recently came out is China’s New Strategy for Waging the Microchip Tech War: read the whole thing.)

This week brings us to the topic of submarine cables (and next week, data centers!).

This Week’s The Long View

THE LONG VIEW

Underwater cable contest

By: Manuel L. Quezon III – @inquirerdotnet

Philippine Daily Inquirer / 04:30 AM May 10, 2023

Early in February the island of Matsu’s two cables linking it to Taiwan were cut: first by a fishing vessel, then by a cargo ship.

The island is the closest outpost of Taiwan to the Chinese mainland. Excused as “accidents,” the incidents coincided with increasing tensions as the rhetoric emanating from Beijing against Taipei and Washington escalated and underlined the vulnerability of global internet traffic to disruption.

This has been an increasing source of concern since January, 2022, when the Svalbard Undersea Cable System which links mainland Norway and the Svalbard archipelago in the Arctic Ocean was cut: suspicions fell on Russia, which had been complaining that a Svalbard-based satellite facility was tracking its submarines. The incident reminded observers of a 2014 action by Russia preceding its annexation of the Crimea, when it damaged cables connecting the area to the rest of Ukraine.

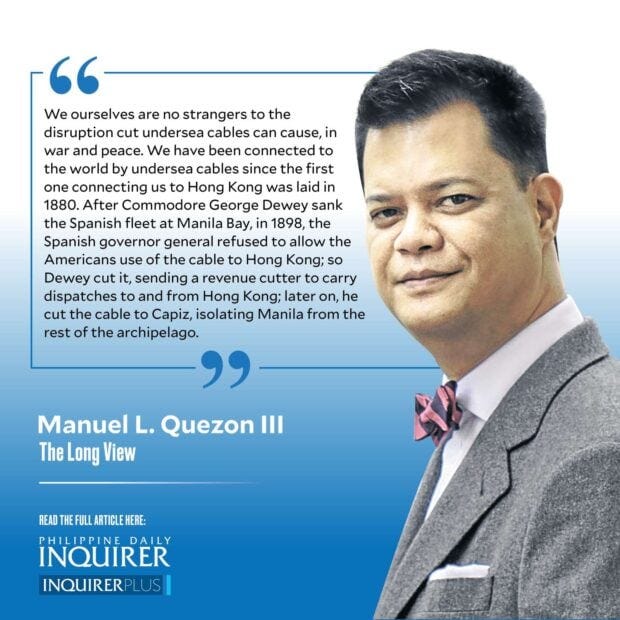

We ourselves are no stranger to the disruption cut undersea cables can cause, in war and peace. We have been connected to the world by undersea cables since the first one connecting us to Hong Kong was laid in 1880. After Commodore George Dewey sank the Spanish fleet at Manila Bay, in 1898, the Spanish Governor-General refused to allow the Americans use of the cable to Hong Kong; so Dewey cut it, sending a revenue cutter to carry dispatches to and from Hong Kong; later on, he cut the cable to Capiz, isolating Manila from the rest of the archipelago.

Back in 2006, the vulnerabilities of the undersea cable system were demonstrated when a massive earthquake off Taiwan affected over 120 call centers: they were totally cut off from their clients on the day of the earthquake, with capacity still down by 40 percent three days after the quake. Most recently in 2010, “terrorists also cut cable lines near Cagayan de Oro,” according to the Maritime Awareness Project.

Back in 2006, all our internet systems connect to the outside world from a single point, somewhere in the vicinity of Batangas. Since then, the number of cables has increased, not least because, as relations between America and China soured, funds were diverted to beef up the networks with friendlier countries, including the Philippines. Submarine Networks says that “today 11 in-service international submarine cable systems connecting the Philippines, and another 6 transpacific and intra-Asia subsea cables under construction,” adding that, “By 2024, there will be 7 trans-pacific subsea cables connecting the Philippines to the US.” Last week we looked at the rivalry between the US and China—involving the American-led effort to deny China advance microchip technology and capacity—is also manifesting itself in another rivalry forcing nations to take sides. Here is a revealing case. The Pacific Light Cable Network (PLCN) began as a Chinese majority-owned submarine cable system initially designed to connect Hong Kong, Taiwan, the Philippines and the US. PLDC (Pacific Light Data Communication) also had two major American partners: Google and Meta (formerly Facebook). In 2020, Team Telecom of the US Department of Justice recommended disapproval of its undersea cable connection to the US. So Google and Facebook refiled their application to connect Taiwan and the Philippines to the US, abandoning the Hong Kong portion, and “without ownership and control by a Chinese entity.” By January 2022 this was approved and in February, the Dr Peng Telecom Media Group, a Chinese stakeholder in PLDC, sold its stake at a loss, replaced by a Canadian investor.

There were other repercussions to the Team Telecom announcement. Between September 2020 and March 2021, three transpacific cables projects to Hong Kong withdrew their US landing applications, while two new cable projects: Bifrost (with Facebook, Keppel, Telin as partners) connecting the US west coast, to Guam, Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines and Echo (Facebook, Google as partners) connecting the US west coast, Guam, Singapore, Indonesia were announced.

For its part, China has been withholding cooperation on undersea cables. Last February, it left South East Asia–Middle East–Western Europe 6 (or Sea-Me-We 6) consortium; instead, China Telecommunications Corporation (China Telecom), China Mobile Limited and China United Network Communications Group Co Ltd. (China Unicom) announced a Europe-Middle East-Asia (EMA) undersea cable project to link Hong Kong to Hainan, “before snaking its way to Singapore, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and France,” Reuters reported last month. HMN Technologies, (majority owned by Huawei Technologies) would make and lay down, the cable, with industry analysts saying this might prevent “some parts of the world” from purchasing capacity in the cable because of this. Reuters had already declared last March that the US and China were waging war beneath the waves.

The year before, China Telecom and China Mobile, which had a combined stake of 20 percent, withdrew from a project linking Asia with Europe when a US company was contracted to build it. The US for its part has rejected “several” cable projects that either involved Chinese companies or directly connects mainland China or Hong Kong to the US on national security grounds (Chinese law requires their businesses and organizations to share data with the government when national security is invoked).

China includes undersea cables in the Digital Silk Road portion of its Road and Belt Initiative. This strategic vision is what makes otherwise odd schemes such as Chinese interest in building a “smart city” (and other proposals, such: an industrial park and an airport expansion) on remote Fuga island, which is administratively part of Aparri, make sense. A Guardian article recently reported that our military, alarmed, decided to establish a naval base there instead; now there is talk of its possible use as an Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement site. Fuga is in the Bashi Channel which separates us from Taiwan, and which, in fact, remains disputed between Taiwan and the Philippines since the 1930s, and where China has been sending its air force to do exercises over the channel.

Five days ago Biz Buzz pointed to Boracay where Dennis Uy had packaged a 2018 deal in which KT Corp. of Korea put up public WiFi in parts of the island, throwing in 40 CCTV cameras for the use of the local government. The system was meant to use the (then nonexistent) infrastructure of Uy’s Converge ICT, which is finally in place. I’ve followed Uy’s zigzagging efforts and China Telecom’s frustrated efforts to come in as the third player in our telecoms, for years in this space, but note that Uy of Converge is different from Uy of Dito.

Converge is a partner (with China Mobile International Limited, China Unicom Global and PPTEL SEA H2X Sdn. Bhd.; HMN Technologies Co., Ltd.) in a submarine cable project to link the Philippines, Hong Kong, China, Thailand, East Malaysia and Singapore by 2024 called South East Asia Hainan-Hong Kong Express Cable System (SEA-H2X). This contrasts with it merely buying access to Keppel Telecommunications & Transportation’s Bifrost Cable System connecting Singapore, Indonesia, and the Philippines, to the US West Coast. Last February, construction of the landing station for this cable was begun in Davao City.

The same Biz Buzz article mentioned that Dennis Uy is getting into the data center game, with a “big” one to rise in Parañaque with a “multinational player” holding a 40% stake. But this is another fast-growing, strategic arena of competition between China and the US.

[The "other" Dennis Uy's] telecoms firm, DITO, in turn, is part of a consortium with Globe Telecoms, to build the Asia Link Cable (ALC) connecting Hong Kong and Singapore as its trunk and branches to the Philippines, Brunei Darussalam and Hainan in mainland China by 2025. But as we’ve seen, the dividing line moving forward, cable-wise, is Chinese participation.

FYI

In my column I edited one part as there are two Dennis Uys: of Converge and of DITO.

I mentioned the extensive coverage I’ve devoted to telecoms and proposals to let Chinese firms become major players. A sleight-of-hand, legally-speaking, was resorted to after amending the Constitution proved too difficult.

In 2022, 85 years of policy was reversed when the Public Service Act was amended to allow 100% foreign ownership of telecoms. However, Congress retains the exclusive power to grant franchises so any foreign players wanting to either buy out local partners or set up on their own, will have to undergo the pleasurable privilege of lobbying Filipino legislators for their votes.

Anyway you can review my past columns on this subject in a previous edition of this newsletter: Manolo Quezon is #TheExplainer Newsletter - Public Service Act amended from 2022.

Notes on the Philippines and Cables

The Eastern Extension.and Telegraph Co. laid an international submarine cable between the Philippines and Hong Kong in 1880. The 1880 Manila-Hong Kong cable laid by the cable ship Calabaria, it was completed on May 2, 1880 after four moths of work. Stretching 535 nautical miles from Hong Kong to Bolinao, Pangasinan, a 160-mile landline then connected it to Manila.

In the US conquest of the Philippines, over 16,000 KM of telegraph cables were laid by the US Army.

After three decades of mulling over the idea, and a US government survey of the route in 1900, a trans-Pacific submarine cable to connect California and the Philippines, by way of the Hawaii, Midway and Guam, and in 1903, it took a mere nine minutes for a message from New York to go around the world, when Teddy Roosevelt’s congratulations to the people of the Philippines marked the splicing together of the Pacific Cable from Hawaii and the Manila cable together.

Submarine Cable Map 2023 is a magnificent site.

There is the Apricot Subsea Cable due by 2024, composed of Google, Facebook, PLDT, Chunghwa Telecom of Taiwan, and NTT of Japan, connecting Singapore, Japan, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Guam.

There is the JUPITER Cable System consortium composed of Amazon, Facebook, NTT, PCCW Global, PLDT and SoftBank, connecting Maruyama and Shima in Japan; Los Angeles, and Daet, Camarines Norte

There is the Asia Direct Cable (ADC) consortium composed of CAT, China Telecom, China Unicom, PLDT, Singtel, SoftBank, Tata Communications and Viettel, connecting Hong Kong and Guangdong Province, Japan, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.

See 49security, Securing the Deep: Undersea Cables and National Security.

The “undersea war”

Britain relied on the undersea cable system it dominated not just to communicate within its empire, but to maintain a global intelligence surveillance system.

John Arquilla, in a March 23, 2023 Hoover Institution essay:

Although radio communication was improving at the same time—Marconi’s first transatlantic transmission took place in December of 1901—the British had a good sense of how vulnerable radio waves were to jamming or listening in. Other countries clearly felt the same, and a number of nations began to build their own undersea cable networks. However, when the Great War erupted in 1914, Britain used its naval mastery to cut the cable of the Germans, severing this link to their colonies in Africa and the Far East, as well as to neutrals in the Americas. Indeed, the British attack on the German cable system forced the latter to depend upon the Swedes for international cable-communication purposes…

A secret war is being fought in the Asia-Pacific. But rather than bullets and bombs, the weapons are digital, and the goal is to control the world’s flows of Big Data.

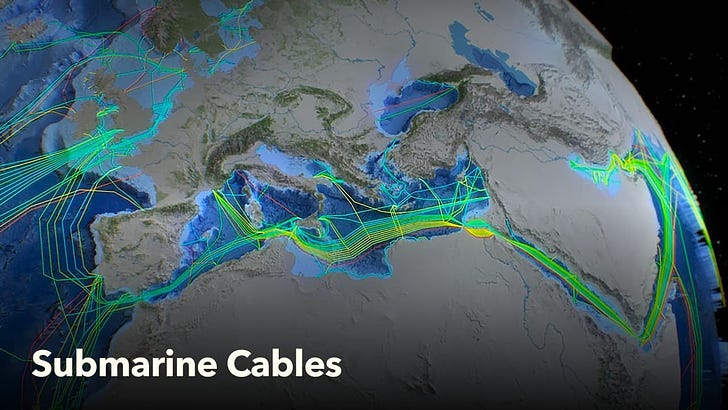

Over 486 undersea cables carry over 99% of all international internet traffic globally, according to the Washington-based research firm TeleGeography. The bulk of them are controlled by just a handful American technology giants, namely Alphabet, Google’s parent company; Meta – the owner of Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp; Amazon; and Microsoft.

Transmitting everything from emails and banking transactions to military secrets, these data flows are even more valuable than oil. With information at the centre of technological innovation, controlling data is recognized as the key to driving economic productivity. As such, the world’s subsea cabling infrastructure is increasingly vulnerable not only to sabotage, but also to espionage – spy agencies can easily tap into cables on their own territory.

That’s why over the last decade, geopolitical rivalry between the U.S. and China has increasingly focused on control of the world’s subsea cabling networks.

Useful readings/visuals:

Taiwan tensions raise alarms over risks to world’s subsea cables (Japan Times/Bloomber 10/31/22)

China Is Practicing How to Sever Taiwan’s Internet (FP, 2/21/23)

After Chinese Vessels Cut Matsu Internet Cables, Taiwan Seeks to Improve Its Communications Resilience (Diplomat, 4/15/23)

From Leveraging Submarine Cables for Political Gain: U.S. Responses to Chinese Strategy (Princeton, Journal of Public & International Affairs, 2021):

China views submarine cables not as a neutral component of a global, mutually beneficial network but as strategic assets which could be tapped or severed in any future conflict (Kraska 2020a, para. 2). Per an official CCP outlet, “although undersea cable laying is a business, it is also a battlefield where information can be obtained” (Starks 2020). This section identifies three threats from China to the submarine cable network, which include the potential for global sabotage and global espionage through the DSR and private sector, as well as the potential for regional sabotage during conflicts including the South China Sea (SCS) territorial dispute... These three threats (global sabotage, global espionage, and regional sabotage) define the scope of U.S. responses to cable insecurity.

Additional readings:

Factsheet: Submarine Cables, in Maritime Awarenss Project.

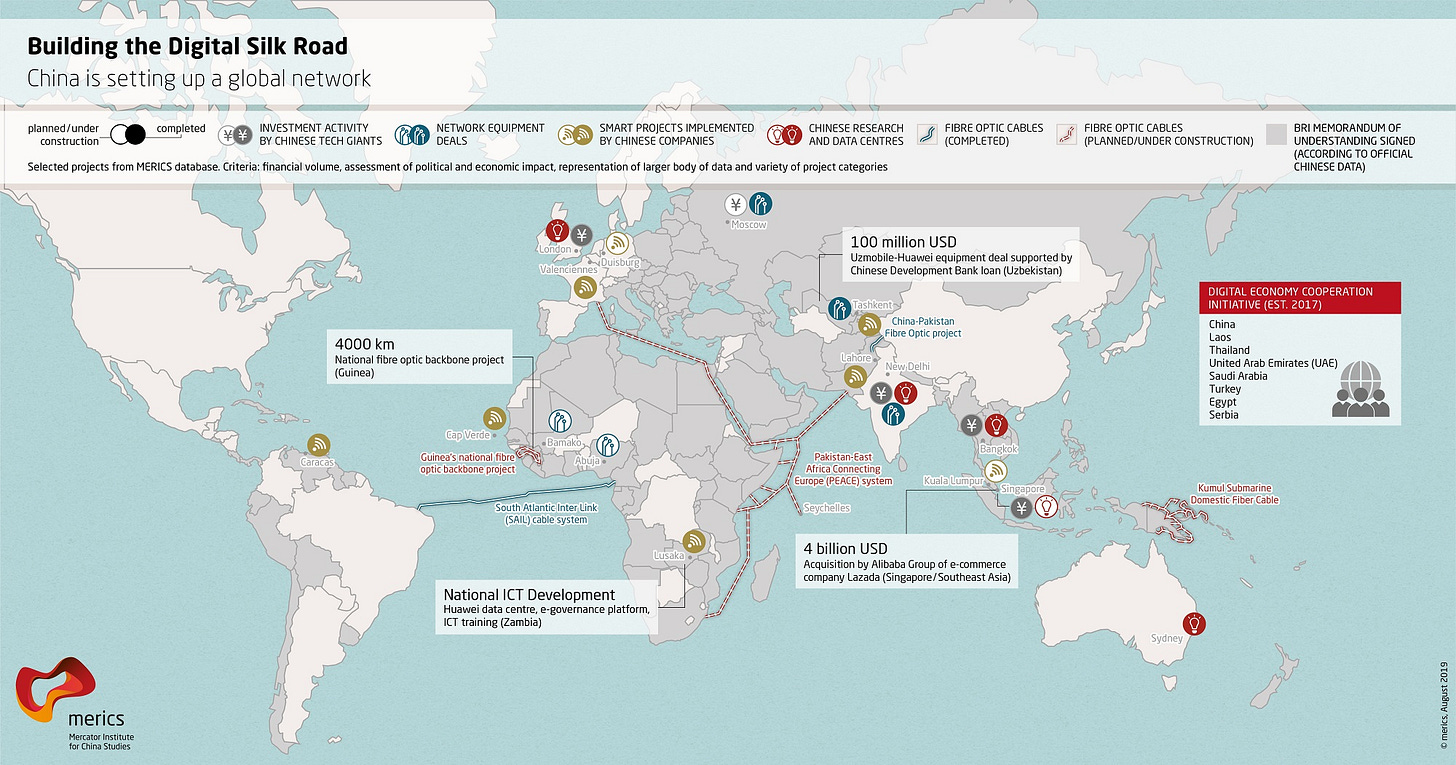

The Digital Silk Road

Digital Silk Road which the German Marshall Fund of the United States in Harvard defines as “the portion of the Belt and Road Initiative focused on enhancing digital connectivity and furthering China's ascendance as a technological power…. [and] to become a world leader in providing physical infrastructure in the digital sphere, exemplified by the Chinese government plans to invest heavily in undersea cables.”

From Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), Networking the “Belt and Road” (2019):

President Xi Jinping’s speech at the Second BRI Forum in April 2019 spoke of cooperation in the digital economy and innovation-driven development as priority areas for the BRI…

What does the digital side of the BRI actually consist of? The Chinese government has greatly expanded the ambition and scope of the Digital Silk Road from its early focus on fiber optic cables…

China’s fiber optic cable and telecommunications equipment industries got clear market share goals in the “Made in China 2025” industrial strategy. Beijing has since aided their international expansion with policy support and massive lines of cheap credit.

As with BRI energy and transport projects, the China Development Bank (CDB), the Export-Import Bank of China (EXIM) and state-owned commercial banks have provided most funding for ICT hardware projects…

Meanwhile, the State Council’s “National Informatization Strategy” (2016 - 2020) called upon China’s thriving private tech giants of the digital economy – Alibaba, Tencent and Baidu – to support the Digital Silk Road while becoming global leaders in areas like e-commerce and mobile payments.

The recent official BRI progress report also speaks of other areas including smart city projects, cloud computing and big data. Expansion in these sectors is politically supported, but state financing for them is not comparable to the hardware projects.

A more detailed summary of the Digital Silk Road’s origins and history can be found in the Council on Foreign Relations’ The Extension of the Digital Silk Road to Latin America: Advantages and Potential Risks. (Juxtapose this with the development of American views on undersea cables, summarized in a recent piece by Joseph Keller from the Brookings Institution.)

A concise look-see can be found in Reconnecting Asia’s Mapping China’s Digital Silk Road (2021):

[I]t is advancing in several areas: wireless networks, surveillance cameras, subsea cables, and satellites. While not exhaustive of China’s digital activities, these activities literally stretch from the ocean floor to outer space, and they enable AI, big data applications, and other strategic technologies. In all four areas, China is gaining globally and positioning itself to reap commercial and strategic rewards, especially as emerging economies grow…

Having grown rapidly at home, China’s surveillance giants aim to dominate global markets. Together, Hikvision… and Dahua supply nearly 40 percent of the world’s surveillance cameras. Only China has companies that are competitive at every step of the surveillance process, from manufacturing cameras to training AI to deploying the analytics. Chinese surveillance technology is being used in more than eighty countries, on every continent except Australia and Antarctica.

China has graduated from being dependent on foreign companies for subsea cables, … to controlling the world’s fourth major provider of these systems. Before being sold to Hengtong Group in 2020, Huawei Marine (a joint venture between Huawei and Global Marine, a U.K. firm) laid enough cable to circle the earth, including transcontinental links from Asia to Africa and from Africa to South America. These connections avoid U.S. and allied territory and could become even more valuable during a conflict.

Completed in 2020, China’s BeiDou system is more accurate than GPS in the Asia-Pacific region and slightly less accurate globally. BeiDou powers a growing list of vehicles, farm equipment, phones, and other consumer products and offers even more powerful services that guide Chinese missiles, fighter jets, and naval vessels. Beijing has begun offering these military-grade services to partners and could use them as a sweetener in the future when selling arms. Strategically, China is reducing its reliance on GPS and increasing the world’s reliance on BeiDou.

Related to this would be in The Power Atlas, the whole thing is interesting but for our purpoaes,

The Belfer National Cyber Power Index measures 30 countries’ cyber-capabilities. It ranks the top ten cyber-powers across the seven objectives it measures in the following order: the US, China, the UK, Russia, the Netherlands, France, Germany, Canada, Japan, and Australia. However, … states’ performance varies a great deal across these indicators. For example, China, France, and even the Netherlands rank above the US on defensive capabilities, pointing not only to the complexity of such capabilities but also to how they might empower smaller states instead of the usual suspects.

Cables: the ties that bind

From Undersea cables in an age of geopolitical competition:

A major factor that complicates undersea cable protection for some states is that they are largely owned and installed by private communications companies, as can be seen by the involvement of Meta and Chunghwa Telecom. Cables are generally financed by consortia of telecommunications firms or, increasingly, tech giants. No individual cable operator is thinking about the system security as a whole or is seemingly thinking about the geopolitical challenges ahead. In addition, private owners have up until now largely showed an unwillingness to take on the costs of enhancing protection measures. Even their governments have not yet given enough thought to mitigating the risks of attacks on this infrastructure or how control of parts of the network could be geopolitically charged.

The private ownership of undersea cables has meant that many governments, until very recently, have not taken the same active role as in other strategic industries, such as energy and shipping. Moreover, because undersea cables “fly no flag” (i.e., they are mostly private concerns), they are not legally associated with any particular state. This complicates the status of cables under international law. The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), for example, in no way prohibits states from treating undersea cables as legitimate military targets during wartime.

The case study here is suggested by the Wall Street Journal article, America’s Undersea Battle With China for Control of the Global Internet Grid: Chinese company Huawei is embedding itself into cable systems that ferry nearly all of the world’s internet data.

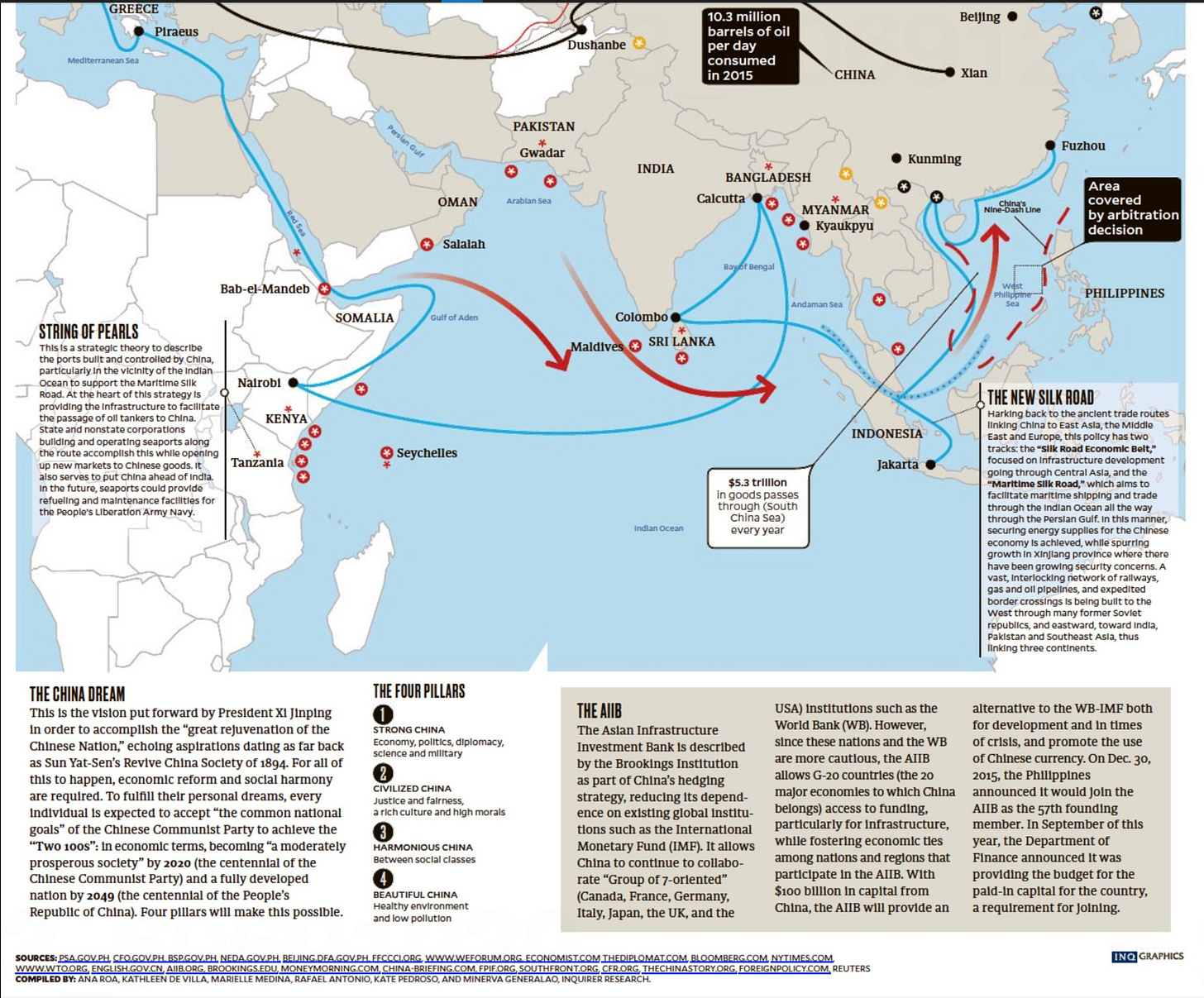

Huawei is the lead in the Pakistan East Africa Cable Express (PEACE) project, the Arctic Connect, and in the Pacific. PEACE is supported by strategic moves such as China taking control of the Pakistani port of Gwadar (thorugh a Chinese firm assuming operations), and the construction of China’s first overseas military base in Djibouti City, where the landing station for the cable is located.

The existence of the sole overseas Chinese base in Djibouti is misleading. At first blush, the contrast between the US and its allies, and China (and Russia) is totally lopsided.

Consider the islands China has created in the South China Sea/West Philippine Sea. You may have heard of the first island chain. This is the chain of islands composed of Japan, Taiwan, (parts of) the Philippines and Indonesia which serves as the American first line of defense (sometimes compared to a string of unsinkable aircraft carriers) and containment cordon for China, and which China, in turns, considers a kind of strategic noose around its neck which the West could tighten at will unless deterred. Back in 2016, China started holding exercises for its air force in the Bashi Channel, ; The Diplomat has called it” a strategically pivotal waterway, marking the rim of what Asian security analysts call the first island chain–the chain of major archipelagos running down the eastern Asian frontier.” A Yomiuri Shimbun article is instructive:

The U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission… stated in its annual report released in December 2020 that the Chinese military in the next 10 to 15 years “aims to be capable of fighting a limited war overseas to protect its interests in countries participating in the Belt and Road Initiative,” and that by mid-century, it “aims to be capable of rapidly deploying forces anywhere in the world.”

The report stated that there were 94 ports around the world partially owned or operated by Chinese firms as of February 2020…

The U.S. Defense Department in a 2021 report … listed 14 countries… as locations that the Chinese military has considered for developing “bases or military logistics facilities.”

Regarding China’s move to assist the development of Cambodia’s Ream Naval Base, the report stated that the move indicates that China’s “overseas basing strategy has diversified.”

In 2017, China established an overseas military base at Doraleh Port in the East African nation of Djibouti..

In the Indian Ocean, where China values sea-lanes to the Middle East, Beijing has been encouraging the development of ports in Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Bangladesh. It is part of China’s maritime strategy dubbed the “String of Pearls,” linked to the aim of restraining India, which has border disputes with China.

China has effectively gained control of the southern Sri Lankan port of Hambantota… Sri Lanka became unable to repay its debts.

China is also extending its reach into Pacific island countries. A security agreement it signed with the Solomon Islands in April is believed to allow China to dispatch its military and security forces and have naval vessels call there….

For China, the establishment of a military foothold in the South Pacific would enable it to conduct operations in waters beyond the “second island chain”...

Back in 2016 my team put together an Inquirer Briefing on China’s 21st Century Dream, which included this map:

Two aspects of it, the “New Silk Road,” and the “String of Pearls” are relevant again today. A good source of comparative maps are Big Think’s The World’s Five Military Empires (2017) and David Vine’s historical maps of US Bases Abroad over time. Just this week, SCO vs NATO: The Struggle to Reshape the World in the Asia Sentinel makes for timely and necessary reading.