The stunted Filipino: A Permanent Underclass

A continuing emergency is condemning millions before they can even enter school

There is stunting, there is wasting, and there is being underweight. The WHO definitions are:

Stunting is the impaired growth and development that children experience from poor nutrition, repeated infection, and inadequate psychosocial stimulation. Children are defined as stunted if their height-for-age is more than two standard deviations below the WHO Child Growth Standards median.

Child wasting refers to a child who is too thin for his or her height and is the result of recent rapid weight loss or the failure to gain weight. A child who is moderately or severely wasted has an increased risk of death, but treatment is possible.

Child underweight belongs to a set of indicators whose purpose is to measure nutritional imbalance and malnutrition resulting in undernutrition (assessed by underweight, stunting and wasting) and overweight.

Back in 2009 I wrote an entry, Republic of Sisyphus, based on a visit to a school on February 19, which included this portion:

Before the program started, I had a chance to talk to some of the teachers and the principal about the situation of the school, which has long had a very good reputation for the excellence of its teaching, teachers, and the scores and marks the students obtain in contests and national tests.

One thing she told me about bothered me. The PAGCOR has a feeding program in the school, which helps 50 malnourished kids. Assistance is to the tune of 30,000 Pesos a month, at 30 Pesos a meal. Now what bothered me was the arbitrary nature of the program (stuck at 50 kids, irrespective of the actual incidence of malnutrition in any school; my impression, though the principal didn’t say it, is that there’s simply a quota of 50 kids per school, so that PAGCOR can provide assistance to many schools). The program has a limited duration, 120 days. The principal said, when I asked her what this sort of limited assistance accomplished, that the program, ideally, rescues kids and restores them to health; that afterwards, hopefully, parents can be convinced to devote more of their resources to feeding their kids.

The principal added that there are other projects taking place at the same time, with various sources of funding, both local and national (noodles, nutritious bread and milk, etc.) but they all have limited durations and teachers just have to hope it helps some but not all. The programs require ingenuity, too; the school has taken to planting vegetables to keep the costs of subsidized meals low, for example.

In my column, Permanently poor (February 23, 2009) I returned to the topic:

In December 1971, some of the country’s leading analysts met in Singapore and discussed the Philippine situation. Sixto K. Roxas, who had played a prominent role in the Macapagal administration, said that the average Filipino was 40 percent better off in 1960 than in 1950 and furthermore 75 percent better off in 1970 than in 1960. This accounts for the nostalgia many people who can remember the ’50s to the ’70s feel for that era in our national life.

What’s happened since then?

For one thing, we’re far more plentiful. We went from 37.9 million in 1971 to 55.8 million in 1986; and from there, climbed to 71.8 million in 1996 and then 85.5 million by 2005, with a population expected to reach 93.7 million by 2010.

With that comes all sorts of problems of adjustment, where the majority are fully used to conditions that make for little privacy while the minority used to keeping the majority at arms’ length find it increasingly difficult to do so, and who themselves, as the managerial and political class of this country, still operate from the assumption everyone knows each other when this cannot and should not be the case any longer.

If we try to answer the same question Roxas addressed, we can refer to the Human Development Index (HDI) which was devised, according to the online reports of the 1st Asia Economic Forum of the University of Cambodia, “as one means to facilitate making comparisons between nations on their relative states of development.”

The result is what it calls a” “three-dimensional” indicator of a country’s overall achievement in helping its citizenry have: a long and healthy life; a depth of knowledge and understanding about the world around them; and a decent standard of living.”

The Asia Economic Forum broke down our region into four clusters. Cluster 1: Australia (HDI Rank 3), Japan (11), New Zealand (19), Hong Kong (22), Singapore (25), South Korea (28) and Brunei (33). Cluster 2: Malaysia (61), Thailand (73), Philippines (84) China (85). Cluster 3: Vietnam (108), Indonesia (110) and Mongolia (114). Cluster 4: India (127), Burma (129), Cambodia (130) and Laos (133).

The AEF observed a “general upward trend in HDI values over the past almost 30 years.” And pointed out that there were the following major points of interest: “the “Asian tigers” (Hong Kong, Singapore and Korea) clearly became part of Cluster 1 over the period prior to 1995; the Philippines has progressively dropped since 1975 to a relatively low position in Cluster 2; and Mongolia has transited from Cluster 2 to Cluster 3 over the period 1985-1995; whilst China has done the opposite since 1995.”

In other words the average Filipino, if you adopt the HDI, has been experiencing a progressive deterioration from 1975, four years after Sixto Roxas made his observations, until the present.

Since the AEF situated the Philippines in terms of our neighbors, our rankings have been dropping even further, from 84th when the AEF looked at figures, to 90th out of 177 countries with data as of 2005, the last reported findings of the UN.

In terms of HDI value, we’re 90th, between Ecuador and Tunisia. If you look at the measurements that comprise the HDI, we’re also 90th in terms of life expectancy at birth, between Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and Cape Verde. In terms of adult literacy rate as a percentage of those over 15 years old, we’re 46th, between Thailand and Singapore. If you look at combined primary, secondary and tertiary gross enrollment ratios, we’re 54th, between Bulgaria and Dominica, while looking at GDP per capita, we (at $5,137 per person) are between El Salvador ($5,137 per person) and Azerbaijan ($4,945 per person).

I picked up the thread so to speak in my column again, in The end of social mobility (February 26, 2009). The point I made then is one I have returned to, time and again, not least because what I obwerved in 2009 found its political fulfillment in 2016:

But this development ignores, too, the rise, or return, if you will, of a permanent underclass of the very poor, who are essentially unemployable domestically or abroad, unless by means of patronage by officials of the state...

Last year a sign of the times was Senator Imee Marcos trumpeting her father’s nutribun project, which led to fact-checkers calling her out since the Nutribun was actually an American scheme.

This week’s Proyekto Pilipino is on a topic that few think about but which represents a continuing emergency for the country.

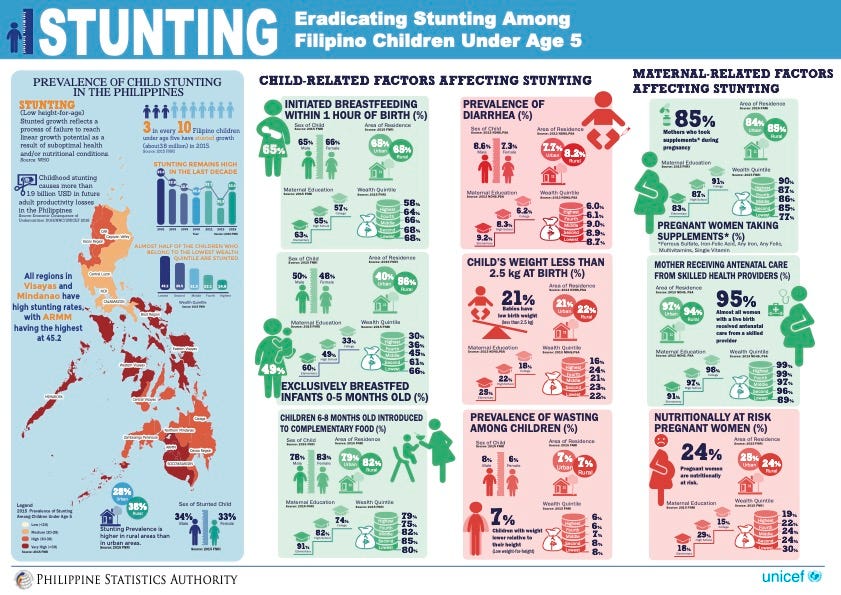

“As of 2015, 1 in 3 Filipino children under 5 years old is stunted, and will never reach full brain and physical development potential.”

Stunting continues to be a very pressing issue until today—but why are we not talking enough about it? Why are we not doing more to resolve this?

In this episode, Fr. Tito Caluag and his trio of distinguished thinkers—Manolo Quezon, Leloy Claudio, and Carlo Santiago—talk to Dr. Ciel Habito, an economist and professor who has been advocating strongly against stunting and the issue of hunger in Filipino children. The issue has deep roots, and just like poverty, requires an all-nation approach. The question now is whether the public and private sector, and every individual, will contribute to help solve this.

“The measure of our effectiveness is a smile on a child’s face. At ang bata, hindi makakangiti kung gutom at kulang sa nutrisyon. ’Yun ang dapat nating gawing batayan kung napapaunlad talaga natin ang ating bansa.”

Some readings

Much as the the Philippine Center for Population and Development might dispute it, statistics have actually improved over the years. Take a look at the abstract of this 1997 paper, Age-specific determinants of stunting in Filipino children:

This study identifies age-specific factors related to new cases of stunting that develop in Filipino children from birth to 24 mo of age. Data come from nearly 3000 participants in the Cebu Longitudinal Health and Nutrition Survey, a community-based study conducted from 1983 to 1995. Length, morbidity, feeding and health-related data were collected bimonthly during home visits. Stunting (length >2 SD below the WHO age- and sex-specific medians) occurred in 69% of rural and 60% of urban children by 24 mo of age. We used a multivariate discrete time hazard model to estimate the likelihood of becoming stunted in each 2-mo interval. The likelihood of stunting was significantly increased by diarrhea, febrile respiratory infections, early supplemental feeding and low birth weight. The effect of birth weight was strongest in the first year. Breast-feeding, preventive health care and taller maternal stature significantly decreased the likelihood of stunting. Males were more likely to become stunted in the first year, whereas females were more likely to become stunted in the second year of life. Because stunting is strongly related to poor functional outcomes such as impaired intellectual development during childhood, and to short stature in adulthood, these results emphasize the need for prevention of growth retardation through promotion of prenatal care and breast-feeding, as well as control of infectious diseases.

Here is stunting and recent statistics, as described by UNICEF in 2020:

Stunting is defined as impaired growth and development experienced due to poor nutrition. Children who are stunted are too short for their age. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), childhood stunting is “one of the most significant impediments to human development, globally affecting approximately 162 million children under the age of 5 years. It is largely an irreversible outcome of inadequate nutrition and repeated bouts of infection during the first 1000 days of a child’s life.” Children who are stunted do less well at school and earn lower wages as adults.

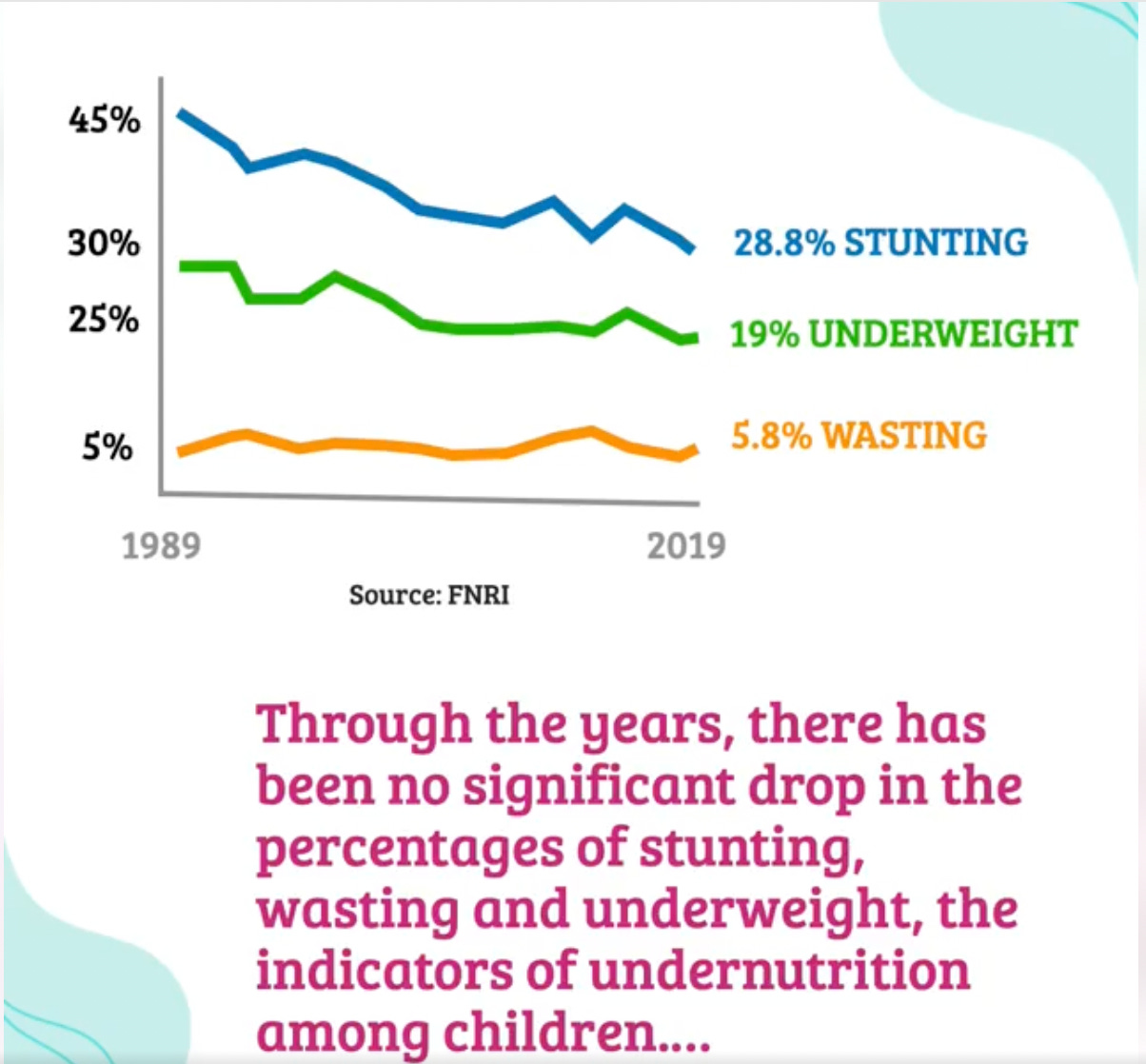

In the Philippines, a third of children are stunted. the Philippines ranks fifth among countries in the East Asia and Pacific Region with the highest stunting prevalence and one of 10 countries with the highest number of stunted children in the world. In the last 15 years, little progress has been made to reduce stunting in the country despite good economic growth and increased health budgets.

The WHO estimates that by 2025, about 127 million children under five years old will be stunted assuming that current trends continue.

See also, an earler (2015) Save the Children study: Sizing Up: The stunting and child malnutrition problem in the Philippines.

The World Bank, referring to its report, Undernutrition in the Philippines: Scale, Scope, and Opportunities for Nutrition Policy and Programming, pointed out these salient facts:

Undernutrition is, and has always been, a serious problem in the Philippines.

For nearly thirty years, there have been almost no improvements in the prevalence of undernutrition in the Philippines. One in three children (29%) younger than five years old suffered from stunting (2019), being small in size for their age.

The country is ranked fifth among countries in the East Asia and Pacific region with the highest prevalence of stunting and is among the 10 countries in the world with the highest number of stunted children.

There are regions with levels of stunting that exceed 40% of the population. In Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao 45% of children below five are stunted, in Southwestern Tagalog Region (MIMAROPA) 41%, Bicol Region it is 40%, Western Visayas 40%, and in the south-central Mindanao Region (SOCCKSARGEN) 40%

Micronutrient undernutrition is also highly prevalent in the Philippines: 38% among infants six to 11 months old; 26% among children 12–23 months; and 20% of pregnant women are anemic. Nearly 17% of children aged 6–59 months suffered from vitamin A deficiency (2018), of which children aged 12–24 months had the highest prevalence (22%) followed by children aged six to 12 months (18%).

Good nutrition is a foundation for economic prosperity, and investments in nutrition are highly cost-effective.

The persistence of very high levels of childhood undernutrition, despite decades of economic growth and poverty reduction, could lead to a staggering loss of the country’s human and economic potential. A Filipino child with optimal nutrition will have greater cognitive development, stay in school longer, learn more in school, and have a brighter future as an adult, while undernutrition robs other children of their chance to succeed.

The burden on the Philippine economy brought by childhood undernutrition was estimated at US$4.4 billion, or 1.5% of the country’s GDP, in 2015.

The country’s Human Capital Index (HCI) of 0.52 indicates that the future productivity of a child born today will be half of what could have been achieved with complete education and full health.

In 2013, it was estimated the benefit cost ratio for nutrition investments in the Philippines at 44 (Figure 3.2). In other words, every dollar invested in nutrition has the potential of yielding a $44 return. A lower estimate projecting the benefits accruing from a nutrition intervention scenario (NIS) at the national level through key nutrition-specific interventions rolled out over ten years at full coverage reaches US $12.8 billion over a 10-year period with a corresponding cost of $1,062 million, yielding a benefit cost ratio of 12:1.

The Impact of COVID-19 on hunger and undernutrition has made it even more urgent for the Government of the Philippines to scale up its efforts to tackle undernutrition.

Hunger in the Philippines rose sharply following the start of the pandemic. Social Weather Stations (SWS) surveys show that in September 2020, after seven months of community quarantine, 31% of families reported experiencing hunger in the past 30 days, and 9% were suffering severe hunger—in both cases, the highest levels recorded in more than 20 years.

It calls stunting the “silent pandemic,” and in a 2021 statement noted for the following:

In some regions, the level of stunting exceeds 40 percent of children under five years of age. This is true in Bangsamoro Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), Mimaropa, Bicol, and Western Visayas. In rural areas, children are more likely to be stunted than their urban counterparts.

Among the primary causes of undernutrition are poor infant and young child feeding practices, ill health, low access to diverse, nutritious foods, inadequate access to health services, unhealthy household environment, and poverty.

According to Nkosinathi Mbuya, World Bank Senior Nutrition Specialist, East Asia and the Pacific Region and lead author of the report, there is only a narrow window of opportunity for adequate nutrition to ensure children’s optimal health and physical and cognitive development. It spans the first 1,000 days of life from the day of conception to the child’s second birthday, he said…

Critical to tackling undernutrition at scale are better and higher levels of nutrition investments as well as adequate domestic financing for nutrition-related programs for vulnerable populations, says the report. Increased direct government funding to and from local government units (LGUs) to deliver on their multisectoral local nutrition action plans to be a priority.

The report suggests several priority recommendations, which if implemented over the next few years can bring about effective and sustainable progress in the Government’s efforts to tackle the persistent challenge of undernutrition in the country.

These include securing adequate and predictable financing for nutrition-related programs to achieve nutrition goals; implementing at scale, an evidence-based package of nutrition interventions that should be made available to eligible households in high stunting municipalities; addressing the underlying determinants of undernutrition through a multi-sector effort, and; ensuring that nutrition is one of the key priorities in the agendas of both the executive and legislative bodies in municipalities.

Such a comprehensive effort would require high-level government ownership and leadership at all levels which would facilitate a whole-of government approach to achieving nutrition results…