My column this week is the third of three parts. The first was on the US’ resolve to maintain its lead in microchip technology: Inviting the Philippines to the Microchip Alliance. The second was on undersea cables as an arena of competition in which allies are increasingly asked to take sides: Submarine cables: An undeclared war. Today’s topic is data centers.

This week’s The Long View:

THE LONG VIEW

Data centers as the third arena

By: Manuel L. Quezon III – @inquirerdotnet

Philippine Daily Inquirer / 04:25 AM May 17, 2023

As Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger puts it, microchips are the new oil—and will be more important than oil and gas over the next five decades. Because of this, the core national interest of the United States is to maintain technological superiority, by denying China the opportunity to catch up in microchip technology. Two columns ago I looked into how this manifests in a growing US- led alliance. In my previous column, I then added a related topic: the ongoing competition between the US and China over submarine cables, with both nations fiercely competing to leverage their diplomatic and commercial power to make countries choose sides.

Today we look at data centers. In previous years, Singapore’s reign had been challenged by Indonesia. The Philippines is now seeking to compete, with PLDT, SpaceDC, the Threadborne Group, YCO Cloud Centers, Beeinfotech, and Globe Telecom, DITO Telecommunity, and Converge ICT engaging with foreign partners. What has helped make data centers increasingly attractive domestically is increased cable capacity as funds originally earmarked for China are diverted to places like the Philippines; a favorable policy environment, a growing domestic market and global-ready workforce, translating to a compound annual growth rate of 11.2% from 2022-2027.

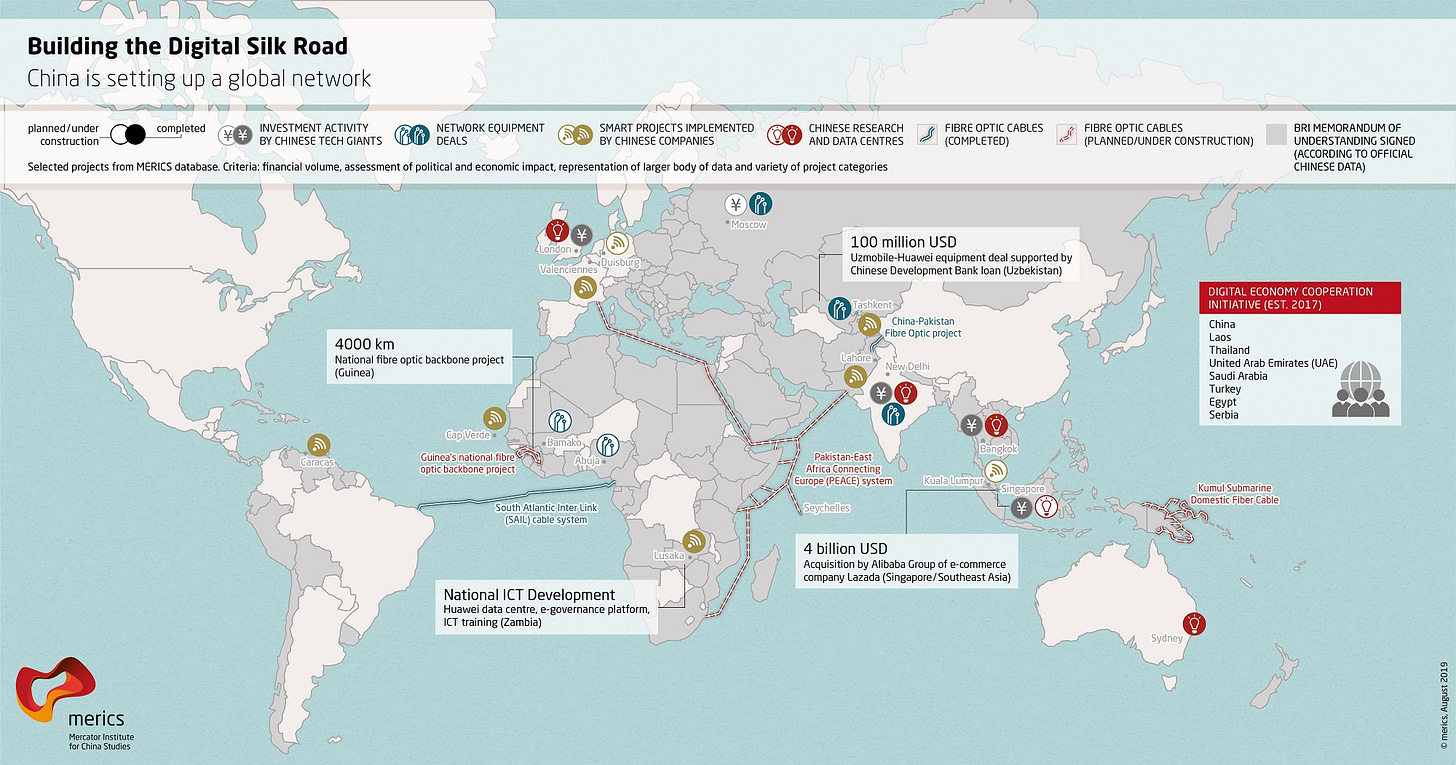

Investments from the US and EU lack the wallop of full state support. The Digital Silk Road component of the Belt and Road Initiative envisions state “investments in telecommunications-network infrastructure, including 5G, submarine and overland fibre-optic cables, satellite ground tracking stations, data centers, whole-of-system integrated solutions such as ‘smart city’ and security-sector information systems, and select ‘over-the-top’ applications such as financial services and processes (fintech) and e-commerce investments.” Untroubled by elections or even, to a large extent, public opinion, China has been able to focus its energies on long-term planning and swift execution.

The battle began over a decade ago. In 2014, Xi Jinping declared that “The flow of information guides the flow of technology, capital and talent,” and that the amount of information controlled has become an important indicator of a nation’s soft power and competitiveness.

Both nations, China and the US, are using their laws to foster their national security. China’s rests on twin planks: a personal Information protection law modeled on the EU’s regulations, and a data security law. according to a commentary by Reva Goujon: “Beijing’s philosophy on data sovereignty rests on several principles: data localization requirements, state oversight and restrictions on cross-border data flows, the right to force transfers of source code, the protection of personal data, and the state’s right to sweeping surveillance powers.”

For its part, as we’ve seen, the US is enforcing an advanced microchip blockade on China, refusing to give landing rights to cables that directly connect to China, and maintains a Bureau of Commerce and Security Unverified List which “subjects foreign firms to strict licensing requirements” as an antidote to China laws requiring companies to share data with the state.

The flow of data itself also brings up national security. Last year, Aynne Kokas’ “Trafficking Data: How China Is Winning the Battle for Digital Sovereignty” was published by Oxford, arguing that a failure of US political leadership, the mania for disruption of Silicon Valley, and Wall Street’s seeking growth at all costs fueled China’s remarkable accumulation of wealth through technology—with Chinese firms quietly mining the US for data to send home. This year’s latest buzzword—artificial intelligence—is leading governments to consider (and act) on its implications. The West is tackling concerns piecemeal; China is taking a much more integrated approach.

A study by our own National Defense College also points out the fourth dimension of the China-US competition: actual military use of cyberspace. Here, China was advanced: for over two decades now I have been referring to how, in 1996, Wei Jincheng published an article, “Information War: A New Form of People’s War” in the Liberation Army Daily of the People’s Republic of China and how this thinking has been implemented over the years from internet espionage, to online brigades to trolls, to the “great firewall of China” and now the Digital Silk Road. Theory has been accompanied by practice: China mobilized hackers as far back as 1999 in revenge for the accidental bombing by NATO of its embassy in Belgrade; in 2007 China demonstrated its capacity to destroy satellites in space and Russia did so in 2021 (China is also building the BeiDou Navigation Satellite System to rival GPS).

More on data centers:

China’s domestic ambitions, known as “Eastern Data, Western Computing,” see China Briefing’s China’s Big Plan to Boost Data Center Computing Power Across Regions:

A major new infrastructure and development plan aims to expand the scope of China data centers to improve the country’s data processing, storage, and computing capacity…Through this, China hopes to correct the imbalance in supply and demand of computing capacity, create greener and more energy-efficient data centers, and boost the country’s overall computing capacity to aid the country’s digital transformation and technological development.

Some interesting context to the above comes from Why does China want to build a national data center system by 2025?:

This isn’t China’s first attempt to redistribute key resources by way of a grand plan that involves heavy upfront infrastructure investment. But it is the first one that’s centered around data and computing power.

In the first decade of the 2000s, the country successively launched three projects to redistribute natural gas, electricity, and water from one Chinese region to another to achieve economic growth: the “West-to-East Gas Transmission Project,” the “West-East Power Transmission and Conversion Projects,” and the “South-to-North Water Diversion Project.” The logic was to pool resources and demand to make better use of limited resources, such as sending water from the wet south to the dry north, and channeling gas and electricity from the resource-abundant west to the populous east.

The caption to the map above has a link you should click on, to read the 2019 Merics briefingon the Digital Silk Road, the infrastructure spending China has committed to, and how Chinese tech companies are being called upon to help fulfill the country’s goals.

For another overview of China’s interests, see The Digital Silk Road: Introduction via International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS):

But the DSR has received little attention compared to the BRI, and it has not been examined as broadly or as deeply as its parent initiative. It remains poorly understood, both as a government initiative and a commercial endeavour. It is difficult even to define the parameters of the DSR; the little official documentation that exists is ambiguous and sometimes contradictory. Some government documents define the DSR as those digital technologies that increase connectivity or help build digital economies, and point mainly to investments in telecommunications-network infrastructure, including 5G, submarine and overland fibre-optic cables, satellite ground tracking stations, data centres, whole-of-system integrated solutions such as ‘smart city’ and security-sector information systems, and select ‘over-the-top’ applications such as financial services and processes (fintech) and e-commerce investments. However, other statements emanating from Beijing include any high technology, such as quantum computing or artificial intelligence (AI) applications for big-data analytics, under the DSR rubric.

See also the Council on Foreign Relations’ Assessing China's Digital Silk Road Initiative. Carnegie Endowment’s Will China Control the Global Internet Via its Digital Silk Road? from 2020. Here is an SSRN study: The Beijing Effect: China's 'Digital Silk Road' as Transnational Data Governance:

China shapes transnational data governance by supplying digital infrastructure to emerging markets. The prevailing explanation for this phenomenon is “digital authoritarianism” by which China exports not only its technology but also its values and governance system to host states. Contrary to the one-size-fits-all digital authoritarianism thesis, this Article theorizes a “Beijing Effect,” a combination of “push” and “pull” factors that explains China’s growing influence in data governance beyond its borders. Governments in emerging economies demand Chinese-built digital infrastructures and emulate China’s approach to data governance in pursuit of “data sovereignty” and digital development. China’s “Digital Silk Road,” a massive effort to build the physical components of digital infrastructure (e.g., fiber-optic cables, antennas, and data centers), to enhance the interoperability of digital ecosystems in such developing states materializes the Beijing Effect. Its main drivers are Chinese technology companies that increasingly provide telecommunication and e-commerce services across the globe. The Beijing Effect contrasts with the “Brussels Effect” whereby companies’ global operations gravitate towards the EU’s regulations. It also deviates from US efforts to shape global data governance through instruments of international economic law. Based on a study of normative documents and empirical fieldwork conducted in a key host state over a four-year period, we explain how the Beijing Effect works in practice and assess its impact on developing countries. We argue that “data sovereignty” is illusory as the Chinese party-state retains varying degrees of control over Chinese enterprises that supply digital infrastructure and urge development of legal infrastructures commensurate with digital development strategies.

Back in 2019, Larry Press asked, Does China’s Digital Silk Road to Latin America and the Caribbean Run Through Cuba? Writing in Strand Consult (Huawei data centres and clouds already cover Latin America. Chinese tech influence is a gift to countries and politicians that don’t respect human rights), Silvia Elaluf-Calderwood zeroed in on Latin America in 2022:

Under the guise of a battle for 5G and taking advantage of anti-USA sentiment, some Latin American governments have welcomed Huawei and Chinese investment. Huawei and China have exploited the USA’s perceived weakness and lack of interest in investment in the region. Brazil, Chile and others have taken, and even courted, Huawei investment to strengthen the cloud and data centre resources. China is now Chile’s top digital trade partner, reflecting a trend prevalent in all Latin America, Huawei investment arm backed by the Chinese government. Brazil and Mexico are important strategic partners for growing Huawei’s ubiquitous presence across Latin America, decreasing further the likelihood of acquiescing to US demands to restrict its technology. Furthermore, China has launched a comprehensive plan of collaboration by extending their Digital Silk Road to the region.

See also China leads investments in African tech infrastructure from 2019 and China plans digital dominance in Africa via Digital Silk Road from 2022.

On the other hand, see Tokyo challenges Beijing as Asia's data center hub: Capacity in Japan's capital forecast to double in 3 to 5 years (Nikkei Asia, 2023).

See Battle hots up for slice of Asean's data centre market (2022):

Data centres are becoming a rapidly growing area of investment in Asean countries, and US and Chinese companies are jostling for a slice of the market.

Analysts say American companies are leading the charge in Asean, but Chinese technology firms are gaining ground…

…Mr Jabez Tan, head of research at Structure Research, which specialises in research on Internet infrastructure… pointed out that as data centre markets in the United States and China reach saturation, companies in these countries are looking abroad to expand.

And South-east Asia, a "geopolitically neutral" region of 660 million people, is a natural target, particularly for Chinese firms, he said.

A core question: Can Chinese Firms Be Truly Private? See the discussion in Big Dsata China, a collaboration between the CSIS Trustee Chair in Chinese Business and Economics and the Stanford Center on China’s Economy and Institutions (SCCEI).

Huawei more than doubled its share of the global market for Infrastructure as a Service, or IaaS in 2020, Alibaba announced over $1 billion earmarked to push cloud computing by training 100,000 developers and investing in 1,000 startups (with the Philippines and Malaysia included), while Tencent also announced its intentions to boost investments in Southeast Asia. Gunning for a greater share of markets is also being accompanied by massive investments at home. Last year, the Eastern Data Western Computing project, kicking off the rollout of China’s Nationally Integrated System of Big Data Centers to put the “entire country on one computer,” while building more facilities in the western part of the country where there is “adequate supply” of electricity: “The hubs in the west will take offline data needs or needs that demand less internet connection, and the hubs in the northern and eastern regions will take more advanced needs from nearby megacities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou,” TechNode’s Qin Chen wrote last year.

From CSIS in 2022: Competing with China’s Digital Silk Road:

The potential for growth in the developing world is vast. Asia and Africa, where demand for international bandwidth is growing fastest, are expected to account for 90 percent of global population growth through 2050.

More recent drivers are accelerating the Digital Silk Road. Chinese suppliers, encountering greater scrutiny in advanced economies, are now doubling down in developing economies. They are also responding to Xi’s call at home to build “new infrastructure,” including 5G networks, data centers, and other digital infrastructure, which will create greater capacity for exporting these systems abroad…

Beijing is hoping Washington is too consumed with domestic challenges to respond. As China builds the systems that underpin communications, finance, and essential government functions in capitals around the world, it is accumulating intelligence and building coercive power. Vulnerabilities are already materializing, from the repeated security failures at the African Union’s headquarters to Papua New Guinea’s data center disaster. Countries aiming to “leapfrog” in their development risk falling into digital dependency. China has already demonstrated a willingness to coerce its partners with other forms of connectivity.

Here however, as the Brookings Institution puts it, “One of America’s asymmetric advantages in technological competition is its ability to develop coalitional approaches for accelerating innovation.” For microchips it has the Netherlands, Japan, and, after some initial misgivings, South Korea on its side to deny advanced technologies to China; for undersea cables, it has also created alliances using landing rights as leverage. And for data centers, it is ratching up the pressure on China. Last year, the US imposed a ban on Nvidia (which controls 95% of the market) selling AI-accelerator microchips to China: this leaves Chinese server farms looking less attractive to clients. Last month, too, Nikkei Asia reported Tokyo making a bid to challenge Beijing aa Asia’s data hub, with capacity expected to double in 3 to 5 years.

Close to two decades of actions have created what’s been called the “splinternet,” an Internet dividing into self-contained continents, instead of the giant, interconnected web it was first envisioned to be. The advocacy by China of eliminating the English-language (and Western character) dominance of internet domains enabled a much more controllable Internet which can also more readily exclude the West For more on the splinternet see The splinternet explained: Everything you need to know; also see Determining the Future of the Internet: The U.S.-China Divergence.

The question of Internet domains almost a decade ago (see China creates own Internet domains from 2008; A URL in Any Language from 2011; ICANN clears 27 non-English domain name suffixes from 2013; Internet Domain Names in China: Articulating Local Control with Global Connectivity from 2015, and Courts, Trademarks, and the ICANN Gold Rush: No Free Speech in Top Level Domains from 2019) was a sign of things to come.

An alliance has formed: Leaked Files Show China And Russia Sharing Tactics On Internet Control, Censorship. As for the Philippines, here’s an insight into public opinion as the country’s leadership zigzags: Southeast Asia under Great-Power Competition: Public Opinion About Hedging in the Philippines.